The story of the first great empire-shaping herring fishery together with historical and scientific speculations on its rise and its fall

SCANIA FISHERY

The county of Skåne, Scania in English, forms the southern tip of Sweden. In the C12th it was part of the Danish kingdom. It provided the base for the first of the great fisheries which led to the Comte de Lacépède’s judgement, The herring is one of those products, the use of which decides the destiny of empires. (Histoire Naturelle des Poissons, 1798).

I: The Great Shoals

Danish Farmers and Viking Traders

The Danes go back a long way with herring. The Ertebølle Culture were throwing away herring boness on Jutland (the top half of Denmark) around 7,000 years ago.

Fast forward 6,000 years, and Danish farmers were well-placed to take advantage of North Sea, Kattegat and Western Baltic herring populations. They caught them in season without feeling the need to become specialist fishermen. At some point in the C11th the King of Denmark lost his lordship over the seas and fishing couldn’t be taxed. Landing was another matter, of course.

Generally in Northern Europe, the demand for marine fish began to increase from the C9th, but around 1000 AD, in what has been called The Fish Horizon Event, it took a leap forward. Who knows but Viking traders, big fish eaters themselves, encouraged consumption in their own inimitable fashion. Either way, dried and salted fish were on their trading product list.

Cod, saithe and ling are relatively easy to preserve. Herring shoals produce far greater surpluses but are high in unsaturated oil. This combines with atmospheric oxygen and the rapidity with which it begins to smell lies at the heart of the herring’s centuries-long comic value. Salt arrests the process of decomposition.

Vikings made their own salt, but it was never a talent for which they received acclaim. It’s not that they couldn’t have mastered the specialist skills, but, at the time, regular sunshine helped considerably in making the best sea-sourced salt. There was plenty in the Bay of Biscay and further south, but distance from the herring grounds made it expensive. On the island of Laesø in the Kattegat, there was salt production from C12th, based on saline groundwater, which is more conentrated than sea water. These days, Laesø salt serves a gourmet market, but it may not have been quite as good in the C12th and, anyway, production capacity was limited.

The Great Shoals

There are so many fish in the Sound that the ships can hardly use their rudders and one can catch them with the hand alone, without the use of any instrument, wrote the Danish historian Saxo Grammaticus (c 1160 – c 1220).

Herring shoals could have a miraculous quality. Their sudden appearances and annual returns were edible signs of God’s bounty. When they failed to return, He was usually punishing bad behaviour. In the wealth of a good herring season, bad behaviour was not uncommon.

Saxo Grammaticus’ miraculous glut in the Sound appears in many herring histories. For traditional accounts it provides an origin story for Scania. It also prefigures the popular account of the fishery’s end: the herrings came and then, one day, they came no more.

Most major herring histories were written by enthusiasts. In case you hadn’t noticed, the herripedia has a similar provenance. Things are changing, however. Proper historians are getting involved and they tend to be more circumspect about miracles.

It has to be said, there was an existing herring fishery in the Sound – the narrow stretch of water between Copenhagen and Malmö, but more importantly from the herring’s perspective, between the Kattegat and the Western Baltic. Just before 1200 AD, centred on the small Skanör-Falsterbo peninsula at its south west corner, this fishery began to develop international significance. At this time Scania was part of Denmark.

The emergence coincided, roughly, with the end of the Medieval Warm Period. Climate change affects fish stocks:

Temperature is a proxy for a range of climatic influences affecting fish stock production, including changes in turbulence, wind mixing, water column stability, movement of water masses from place to place, and light conditions. (The Origins of intensive marine fishing in Medieval Europe: the English evidence, Barrett, Locker & Roberts, 2004)

Herrings are particularly sensitive. Even when they’re not being sensitive they have a practical disposition towards following the plankton, which drifts on the movement of water masses.

The shift in the scale and importance of herring fishing in the Sound may have been effected by supply-side changes (gluts) or, encouraged by the Church’s fasting requirements, by demand-side growth. Or both.

Whatever the cause, the shift required salt.

II: Denmark, Lübeck and the League

The German Hanse

By the middle of the C13th, Lübeck, just across the Baltic from Scania, was at the centre of the emerging German Hanse or Hanseatic League. It was already strongly involved in the Rügen herring fishery, which had salt spring proximity. More importantly, in partnership with Hamburg, Lübeck also controlled the trade routes from Lüneberg’s salt mines. Lüneberg salt was amongst the best produced in northern Europe and there was plenty of it.

The Hanse grew out of German merchant settlements in the Wendish lands of the Baltic. With policies of mutual support and co-operation, Hanseatic cities were technically part of the Holy Roman Empire, but enjoyed considerable independence and used it to build a federated empire firmly rooted in business interest.

They protected their own, challenged arbitrary power, bribed or threatened princes, insisted on favourable trade conditions, imposed and maintained monopolies. As a political unit, they went to war in pursuit of business interests. Membership of the League varied as constituent towns balked at its rules or negotiated trade deals of their own.

Between the C13th and its collapse in the C17th around two hundred towns and cities were part of Hanse – not just in Germany, but in Holland, Flanders and across the trading network. Lübeck was its capital.

It was already trading Rügen herring, but control of salt supplies for the emerging gold rush of the Scania fishery gave it a lever. The Danish crown clearly identified the problem early on. In 1201 the Danes captured a Who’s Who of Lübeck merchants, along with their fleet, while they were visiting the Scania herring fair. They conquered and controlled the city until 1226, when the Holy Roman Emperor declared it a Free Imperial City.

In the shifting and uneasy balance of power the parties gradually came to an arrangement. The Second Danish-Hanseatic War was concluded in 1370 with the Treaty of Stralsund. If it favoured the Hanse, this was just because they won.

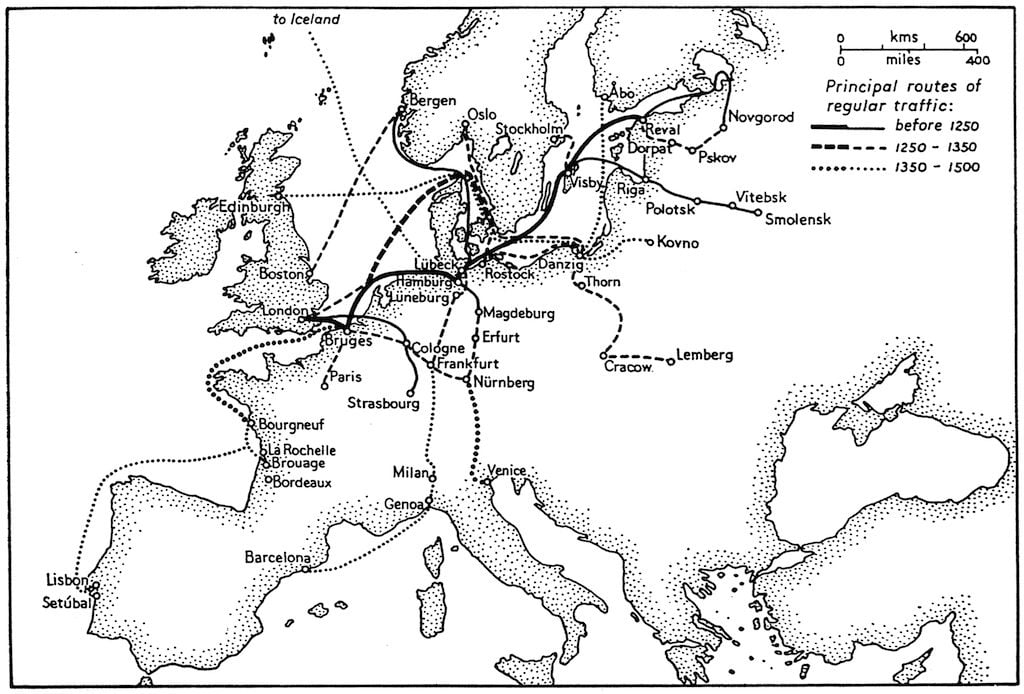

Herring histories have had it that the Danish crown took the taxes and controlled the fishery, whilst Lübeck and the Hanse controlled curing and trade. Carsten Jahnke, in The Medieval Herring Fishery in the Western Baltic (2008), argues forcefully that while the Germans also fished, the Danes also traded. What became known as a Hanseatic trading empire, however, took over the complex of Viking trade routes and added its own.

The network reached east to Novgorod, west to London, north to Bergen, south through the German hinterland to Italy and by sea to the Bay of Biscay and eventually Lisbon.

The Scania Fishery

The importance of the Rügen fishery had declined rapidly, but Scania grew on an organisational model it had provided. Fishermen’s camps or fiskelejer spread out along the foreshore and behind them vitten (curing station pitches) for 26 Hanseatic towns and cities were parcelled out. There were a number of herring fairs, where fish and a range of superficially more attractive international goods were traded. The main one was at Skanör. In the C15th, with the fishery in decline, it transferred to Falsterbo.

In 1375, along with Rome, Venice, Pisa and Florence, Lübeck was named by Emperor Charles IV as one of the five glories of the Holy Roman Empire: an indication of just how wealthy it was at its height. It wielded the greatest influence and its pitch at Skanör had space, not just for fish processing, but a church, a cemetery and its own executioner. The vitten were effectively small colonies for the home cities, each run according to their own laws.

As well as to Danzig, Rostock, Stettin, Stralsund and other German/Wendish cities, 10 of the vitten in Scania belonged to Hanseatic cities in the Netherlands. This could indicate just how much the Dutch loved herring even then, but the scale of their involvement may have played a significance in their later rise as the Comte de Lacépède’s next herring empire.

The fishing was mostly conducted from undecked boats, which could hold up to 2 herring lasts. Depending on size, you got roughly 12,000 herrings to the last. These boats were crewed by between three and six men using drift or set nets. There were Danish, German and Dutch fishermen, but the fishery also drew boats from Norway, England, Scotland and Wales. Those who rounded Jutland, navigating the Skaggerak, were known as circumnavigators (umlandsfahrer).

Fishermen brought their catches ashore daily and had to sell to the merchants there. Unsurprisingly there were attempts at getting round this – the Scots, English and Welsh were specifically forbidden from salting the herring they caught. In 1470 English involvement was forbidden altogether.

Thousands came to work at the Skanör herring fair, working the season from mid-August to early October. As became standard with onshore curing, the gutting, salting and packing was done by women.

Herring fairs in the Middle Ages were viewed much in the same way as the American Wild West, but it wasn’t for lack of regulation. Boats were not even allowed to start fishing until the Bailiff had arrived and delivered a reading of the Motbok with its ever-increasing sets of rules.

Salt and salting were strictly controlled, as was barrel size. Barrel branding acted as a quality guarantee, with an effective system of redress that reached to the far end of trade routes. Jahnketalks of how this gave Scanian herring preferred purchase status across the Hanseatic network.

One day a week, catches could only be bought by the Danish crown. Fishermen were taxed for use of the foreshore: in 1520 this was 10% of the catch plus a boatload at the start of the season. There was an additional tax of 10 pfennigs a last for foreigners and 5 for Danes.

As the fishery had grown Lübeck had opened up salt mines at Oldesloe and taken control of the salt springs on the Pomeranian coast, but by the late fourteenth century they were importing Bay salt from Bourgneuf.

In the C14th there were at least 10,000 boats involved in the fishery. By 1400 there were around 900 herring merchants in Lübeck alone and the town imported in the region of 65,000 registered barrels annually. Production in Scania probably reached 300,000 barrels a year, but by the late C16th it was mostly over. There was still herring fishing, but it was only of regional concern.

III: Did the fishes go or the fishermen?

Decline

The herringist narrative is of the miraculous shoals coming back every year until some point in the C15th. Edgar March, in Herring Drifters, says, very specifically, 1425. Jahnke, who has gone through the records, notes there were bad catches that year and in several others during the C15th, identifying a decline in the fishery from a peak in the decade from 1370. He also, however, points to the herring fairs continuing until Sweden occupied Scania in 1658.

Together with Dollinger (The German Hansa, 1964), but backed by much more herring substance, Jahnke sees the main cause of the decline as the policies of the Wendish Hanseatic cities around Lübeck, which attempted to keep their competitors from the North Sea and the Baltic away from the fairs, which caused the fairs to lose their significance as an international clearing house. In other words, the rise of the Dutch herring fishery, Die Groote Visserye, came because their merchants, forced out of the Baltic, had to build their North Sea operation.

Notwithstanding the bad seasons, Jahnke points to the fact that, Centuries of data demonstrate that herring stocks in the Sound were at a stable level as a general rule; this level sufficed for the demands of the merchants serving the European markets. He argues persuasively, The rise and fall of the fairs of Scania had no biological basis.

IV: A herringist speculates

More things in Heaven and Earth

But… but… but…

If it is anything, the herripedia is a narrowly focused celebration of limitless possibilities. As one of the top Danes at Elsinore-by-the-Sound once said:

There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio,

Than are dreamt of in your philosophy.

It’s important to establish what can be said with any degree of certainty, but there is room here for speculation.

The phenomenon Saxo Grammaticus described has enough form to have acquired a name, stimenbildung. With technological advantages unavailable at the end of the C12th, you can google herring shoal surface video and see one for yourself. Concentrated herring shoals can appear as a kind of boiling of the water. It was just that it was new to Grammaticus.

Neucrantz, on the other hand, writing in 1654, is clear that numbers had seriously declined on the Scania shore. He may have been referring to a set of bad years. And the Baltic herring trade did continue, with significant numbers, into the C17th. But he writes of the decline in a way that suggests there had been no major recovery in his time.

Herrings come and herrings go. It’s in their nature. The problem with herringist accounts of Scania lies in their presentation of a singularity lasting between 300 and 400 years. Historically and economically it would be fair to say an internationally significant fishery came to an end. Who knows what the zooarchaeologists might turn up in the future, but hard evidence for causal, biological factors is in short supply.

Speculatively, however, we can separate the comings from the goings.

The comings

Jahnke links three fisheries in an interactive relationship, Scania, Rügen and Bohüslan. The last of these is mainly focused on ‘herring periods’ roughly every 100 years. They have generally lasted between 30 and 60 years. In early Bohüslan periods, its herring do come down into the Sound, so it’s not beyond possibility that they played a part in Grammaticus’ stimenbildung.

The thinking is, Bohüslan surges are caused by years of particularly strong easterlies, pushing surface water out from the Baltic and creating a counter current. In addition to those already in the Skaggerak and Kattegat, you get North Sea herring.

The end of the Medieval Warm Period could have brought an unusually strong Bohüslan surge, but Barrett, Locker and Roberts suggest, for the 200 odd years it lasted, warmer waters in the North Sea and the Baltic would have depressed herring numbers.

Linking individual physiological indicators to the productivity of fish populations: A case study of Atlantic herring (Moyano, Illing and others, 2020) looked at Western Baltic spring spawners (also known as Rügen spring spawners). Both in the laboratory and in Greifswald Bay, off the island of Rügen, the larvae reacted badly to warmer water. It induces heart arrythmia. The warming waters of the last 15 years have depressed WBSS numbers.

The end of the Medieval Warm Period would probably have seen an increase in Baltic (and North Sea) herring populations. Given that marine fish demand was still growing in the C11th and C12th there might have been enough to satisfy the market, but, at the end of that period, in the narrows of the Sound a concentration of increased numbers would have been particularly visible.

What has traditionally been seen as an arrival of miraculous shoals may have been a return to normal levels. Grammaticus hadn’t seen a stimenbildung before, but previous ones would have been long before he was born – before it represented such a market opportunity, before there was enough salt, before there was much point in recording it.

The goings

The proximity and interaction of Scania, Rügen and Bohüslan enabled a response to a Bohüslan surge or a Scanian bad season, but the links swam deeper.

Herring populations in the Sound are mixed (as are those involved in Bohüslan surges, as are those in the Southern North Sea). Distribution, Density and abundance of the Western Baltic herring in the Sound (2000) by Rasmus Nielsen and others identifies 75% of herring in the Sound between August and March as Rügen spring spawners. They migrate there for winter feeding. The herrings which remain off Rügen during this period are immature: up to three years old.

The Scanian herring fairs ran from August 24th to October 12th. What this means is, if populations have maintained anything like the same relative proportions, much of the catch was of recovering spents. Catching Rügen spring spawners in Greifswald Bay in the spring will give you nice fat herrings: better than spents, even if they were recovering. The rise of the Scanian fishery seems to have been based, therefore, on accessible quantities of fish, not so much on inherent quality.

However good the curing, you can’t make a silk purse out of a sow’s ear. It’s possible Scanian merchants did not conceptualise salt herring as any kind of silk purse, but, as a rule, these Western Baltic spring spawners are in the Sound feeding and recovering until March. The longer they feed, the more they recover weight. The fairs, however, ended in October.

It could be that the fishermen and merchants were keen on the proportion of nice, fat autumn spawners in the catch. At Rügen, there was a set price per barrel, but the fish involved would largely have been of the same quality. Whether the herring barrels at Scania were graded or not, the relative proportions of spring and autumn spawners would have had a market significance.

Neucrantz was considerably ahead of his time in identifying the reality of mixed populations and the questions they posed for the prevailing theory at that time of a single, Grand Migration of the herring. Although he didn’t resolve them, he was clear about the value of spents: Weak and dry, these herrings are only suitable for the lower classes.

The bad seasons in the C15th could have been an indication of overfishing across the mixed population. A population collapse in a smaller autumn spawning population, however, might have had a disproportionate effect, even though catches remained reasonably constant. If it was possible to differentiate what were spawning and feeding grounds, fishermen would naturally be drawn to the spawning fish and 10,000 boats would create pressure on any small population.

Another possible explanation for bad seasons can be found in factors associated with marine water coming into the Baltic, together with temperature, wind and nutrient load. These can deplete oxygen levels in the Sound and the noted effect seems to be particularly pronounced from August to October. In The effects of periodic marine inflow into the Baltic Sea on the migration patterns of Western Baltic spring-spawning herring (2014), Tanja Miethe and others suggest low oxygen levels trigger early autumn migrations from the Sound into the Arkona Sea (the bit of the Baltic between Scania and Rügen).

The herrings would still have been accessible to fishermen stationing themselves on the Scanian shore, but at an increased distance and in open water, the time and effort involved in catching them would have increased.

And the other fish

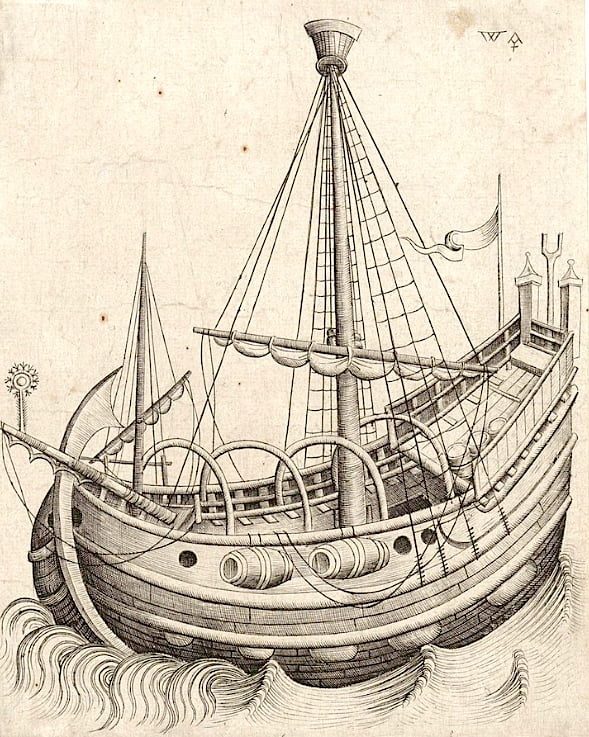

The Dutch built their first herring busses around 1416. An early factory ship, its catches gutted and salted on board, the buss was designed for the exploitation of the North Sea. Scania did not allow onboard processing.

By the 1470s James III of Scotland was fruitlessly advocating buss building by his own countrymen. He could see the wealth being generated in Scottish waters without much if any of it reaching his coffers. Sixty years later James V went to war with the Dutch over fishing limits. The herring became an obsession with the Stuart kings of Scotland and later England.

The Dutch season, enabled by busses which had no need of herring fairs, ran from June 24th off the Shetland coast to November and beyond off Yarmouth and the southern coast of England. This was Die Groote Visserye. It was bigger on exclusion even than the Wendish cities of the Hanse.

Barring the Dutch from the Scanian fishery will have lent a helping hand, but a range of persuasive logics was surely already taking them in different directions. Scottish waters gave them vast shoals of larger spawning herrings. The Dutch made a big thing of their own inshore herring population being unsuitable for salting, even though (or especially because) they won’t have been significantly different from Baltic inshore populations.

It’s legitimate to express a preference for a sweet, smaller herring – the Manx or the Loch Fyne kipper for example. Neucrantz, in Lübeck, loved fresh Western Baltic spring spawners best of all, but recognised Dutch superiority in salted herring. Since the rise of Die Groote Vissereye larger northern herrings, from Scotland, Norway, Iceland or Russia, have overwhelmingly dominated the market.

Allowing the busses to carry on fishing and processing, at the outset of the Dutch season, fast ventjagers – small ‘sale-hunting’ boats – raced back to the home port for the vastly inflated prices that were spun out of the first maatjes, ‘virgin’ spawners. The Dutch marketed a delicacy out of plenty. There will have been plenty of virgin spawners at Rügen, enough at Scania, but the Dutch turned them into theatre. Beyond the hoopla of ventjagers, the great Dr Nicolaes Tulp, corresponding with Neucrantz, wrote of the first barrels of the season garlanded and ceremonially carried into inland towns and villages.

The Hanseatic merchants made a thing of quality control, but in the Low Lands they cultivated secrecy and mystery around gutting and curing. They promoted the legend of an innovator in Willem Beuckels, an origin story that spoke of quality rather than quantity.

Part of the secrecy was not actually letting on what the innovation had been. There was a pickiness in the materials – moor salt, bay salt, not Lüneberg’s rock salt, but today’s zooarchaeologists comparing Scanian and Dutch gutting cut marks don’t pick up any significant change in the basic techniques.

They captured the market with earlier product, a fanfare for its higher quality and strictly graded barrels offering differentiated certainty on what was being paid for. They sold good herrings with a good story.

Regardless of the speculation, you can’t help feeling the Wendish cities could have been as laissez-faire as they liked, it probably wouldn’t have saved the international significance of the Scanian fishery.

Acknowledgements & Bibliography

Acknowledgements

This entry on the Scania Fishery has been rewritten extensively, prompted by some generous corrections to the original by Carsten Jahnke. The herripedia welcomes corrections! Together with the papers he also kindly sent, they opened up a whole warren of research rabbit holes. Academia.edu and Elsevier now send links to archaeological, historical and scientific herring and other fish-related papers on almost a daily basis. It is a whole new world…

Bibliography

Jürgen Alheit & Eberhard Hagen The Bohuslän herring periods: are they controlled by climate variations or local phenomena? (1996)

James H Barrett & DC Orton (ed) Cod & Herring, the Archaeology & History of Medieval Sea Fishing (2016) – notably Poul Holm’s Commercial Sea Fisheries in the Baltic Region c AD 1000 – 1600; Lembi Löugas’ Fishing and Fish Trade During the Viking Age and Middle Ages in the Eastern and Western Baltic Sea Regions; Inge Bødker Enghof’s Herring and Cod in Denmark; James H Barrett’s Medieval Sea Fishing AD 500 – 1550

Florian Berg, Aril Slotte, Arne Johannessen, Cecille Kvamme, Lotte Wørsoe Clausen & Richard D M Nash Comparative biology and population mixing among local, coastal and offshore Atlantic herring (Clupea harengus) in the North Sea, Skagerrak, Kattegat and western Baltic (2017)

A Corten A proposed mechanism for the Bohuslän herring periods (1999)

Hans Höglund Long-term variations in the Swdish herring fishery off Bohuslän (1978)

Carsten Jahnke The Medieval Herring Fishery in the Western Baltic (in Beyond the Catch, Fisheries of the North Atlantic, the North Sea and the Baltic, 900-1850, edited by Louis Sicking and Darlene Abreu-Ferreira, 2008)

Carsten Jahnke A Church landscape that disappeared: Hanseatic merchants, churches and the Scanian fairs (in Lund Studies in Historical Archaeology vol 17, 2016)

John Travis Jenkins The Herring and the Herring Fisheries (1927)

Edgar March Sailing Drifters (1952)

Tanja Miethe, Tomas Gröhsler, Uwe Böttcher & Christian von Dorrien The effects of periodic marine inflow into the Baltic Sea on the migration patterns of Western Baltic spring-spawning herring (2014)

Marta Moyano, Björn Illing, Patrick Polte, Paul Kotterba, Yury Zablotski, Thomas Gröhsler, Patricia Hüdepohl, Stephen J Cooke & Myron A Peck Linking individual physiological indicators to the productivity of fish populations: A case study of Atlantic herring (Ecological Indicators, vol 113, 2020

Rasmus Nielsen, Bo Lundgren, Torben F. Jensen & Karl-Johan Staehr Distribution, density and abundance of the western Baltic herring (Clupea harengus) in the Sound (ICES subdivision 23) in relation to hydrographical features (2001)

Bo Poulsen The variability of fisheries and fish populations prior to industrialised fishing: An appraisal of the historical evidence (Journal of Marine Systems, 2009)

Arthur M Samuel The Herring; its Effect on the History of Britain (1918)

See also

- ARCHAEOLOGY

- BEUCKEL, Willem

- BOHUSLÄN FISHERY

- BRITISH FISHERY

- BUSS

- DIVINE PROVIDENCE

- DRIFT OR GILL NETTING

- DUTCH GRAND FISHERY

- EYVIND SKÁLDASPILLIR

- FASTING

- FEEDING

- HERRING BUSS (TUNE)

- HERRING LASSES

- ICELANDIC FISHERY

- MIGRATION & MOVEMENT

- NEUCRANTZ: ON HERRING (1654)

- PICKELHERING

- PROPHETIC HERRINGS

- SALT

- SHOALS

- SMITH, ADAM: WEALTH OF NATIONS

- SOVEREIGN OF THE SEAS

- SPAWNING

- VENTJAGER

- WHITE HERRING