The story of the red herring gag shared between Shakespeare, Jonson & Nashe in at least six great literary works

RED HERRING JOKE, THE

Good belly laughs are rare in the anatomising of a joke, but anatomise we must: this is literarily the greatest joke of all; in its presence, all others fade. And the red herring is smoked at the heart of it.

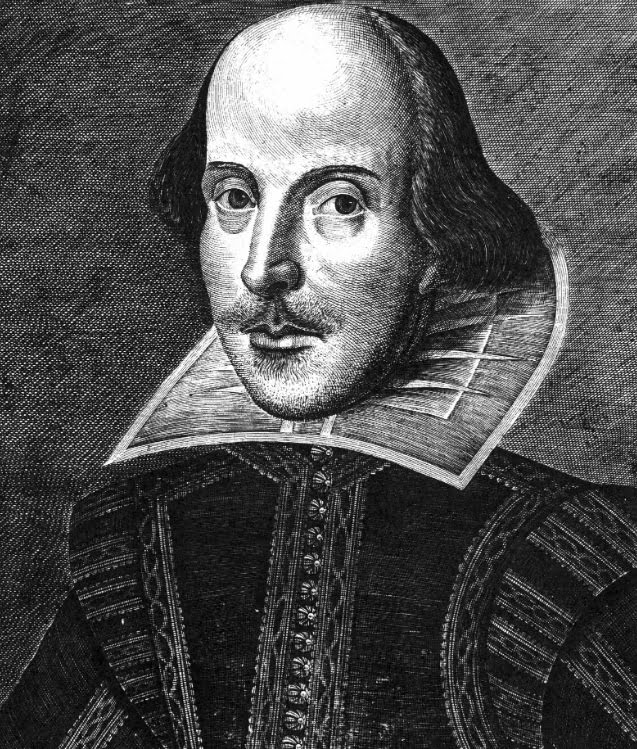

It may not begin in the best of taste, but it builds and it has major league provenance (William Shakespeare, Ben Jonson, Thomas Nashe). The story which unfolds with and around it is intriguing and ultimately moving. First, though, the gag: why is a religious martyr like a red herring? Because he’s been hung and well-smoked.

Boom! Boom!

Well, that’s the gist of it. Did Nashe crack it first? He wrote The Unfortunate Traveller in 1594, a picaresque proto-novel littered with hangings, rarely celebrated for its good taste. The joke’s detail, initial context and timeline point to Shakespeare (and Titus Andronicus,also from 1594, isn’t exactly a master class in good taste). Jonson was just getting going, but his satires can be savage enough for anyone. It may have emerged collectively (possibly in an alehouse): each of them took pride in his wit and each uses it with a sense of ownership.

The exploration, here, of Nashe’s use of the joke is over twice as long as that of Shakespeare’s and Jonson’s put together, but his delivers the greatest herring work in English literature.

Political Context

Its origin can be dated with reasonable precision to late 1596/early 1597. The Lord Chamberlain’s Men, the company Shakespeare wrote for and in which he had shares, was founded in 1594. Henry Carey, 1st Baron Hunsdon, was Lord Chamberlain. Gaffer to the Master of the Revels, his was not patronage to be sneezed at. Henry’s son, George, was happy to continue the relationship with the players and he wanted to be Lord Chamberlain, but when Henry died in 1596, the job went to William Brooke, Lord Cobham.

Back in the 1570s William Brooke had had his own company of players, but his cultural positions seem to have hardened. The appointment might have been a signal from those on high. A little wit can be a dangerous thing and some at court thought the theatres and the satirical pamphleteers had been stepping over the line, stirring up discontent. The Brookes were from the Puritan end of the cultural spectrum and The Lord Chamberlain’s Men had to become just Lord Hunsdon’s Men. They wouldn’t have been alone in registering alarm at a possible power shift.

Jonson actually converted to Roman Catholicism in 1598, but various of the patrons Shakespeare and Nashe shared had Catholic sympathies. As well as the Careys, Henry Wriothesley, Earl of Southampton and Ferdinando Strange, Earl of Derby, played the line, at times dangerously. Strange was probably poisoned in 1594, either by Catholic plotters he’d betrayed or agents of a state which still didn’t trust him.

The state’s concerns were complicated. Elizabeth had re-established the Church of England with herself at its head; Spain and Catholic Europe posed an active external threat; Recusant English Catholics were perceived as an internal threat; Puritans in the 1590s were setting up their own churches, whilst agitating for more radical change than was being offered by the C of E. To cap it all, by the late 1590s the Virgin Queen was perceived to be ageing and all parties were focusing on the impending succession. Stakes were high and lines were tricky.

Critical Context

There’s a whole industry in Shakespeare criticism. Plenty is written on Jonson. Nashe gets a byline in English Literature. On the basis of his red herring output alone, he deserves better. In all the extraordinary breadth of learning English literary studies draw upon, herring lore is sadly under-represented. This may have affected a full appreciation of the red herring joke. Most interpretations proposed here have either been acknowledged or seem self-evident. One or two are a little speculative.

Anatomy of a Joke, Pt 1: Shakespeare

Henry IV, Pt 1 was first performed in late 1596 or early 1597 by Lord Hunsdon’s Men. Prince Hal’s fat old rogue of a companion was Sir John Oldcastle, who was actually only seven years older than Hal, but had indeed been the young prince’s friend. Concerns about his influence weren’t about roistering, but because he was a Lollard, a proto-puritan Protestant.

After coronation in 1413, Henry V did his best to protect his old friend’s back, but Oldcastle was convicted of heresy. He escaped from the Tower of London and burned his bridges, launching a badly-organised rebellion. He carried on plotting until caught in 1417, when he was hanged and burnt, gallows and all, for the original offence.

Oldcastle became Lord Cobham through marriage. Martyr or traitor, he had been alternately praised or mocked in previous Elizabethan works. It’s by no means impossible that William Brooke, who was his direct descendent, had encouraged a pro-Oldcastle production when he’d had his own players. Creating such a roaring libertine out of a Lord Chamberlain’s ancestor was a relatively mild jest, but Brooke wasn’t amused. He complained to the Queen and word came down that the character’s name would have to change. Shakespeare changed it to Sir John Falstaff.

FALSTAFF

There had been a real Sir John Fastolf and audiences recognised Falstaff as a variant. Even closer in age to Prince Hal, Fastolf’s glory days didn’t come until well into the reign of Henry VI, but Shakespeare got two jokes out of the new name. Fall-Staff suggested the 69 year old new Lord Chancellor might not be able to get it up anymore.

On this point, briefly returning to the attribution question, it’s only fair to mention that Nashe had form with limp willy jokes. Writing for his patron Lord Strange, in 1592 he’d produced a long poem The Choise of Valentines, or the Merrie Ballad of Nash his Dildo (to which Mistress Frances, in the end, has to resort). We are, however, primarily concerned with the second joke.

We all know Shakespeare’s Falstaff wasn’t at the Battle of Agincourt (1415) in Henry V,because he’d died in a London tavern, attended by the Hostess. She tells of the piteous scene in Act II. Fastolf, on the other hand, had been invalided out for injuries sustained at the Siege of Harfleur.

His finest hour was not until the Battle of the Herrings in 1429. Against combined French and Scottish forces led by the Duc de Bourbon, Fastolf fought a valiant and successful defence of a wagon train of red herrings and other Lenten stuff destined for English forces at Orléans. The story’s in Holinshed’s Chronicles (1577) and Shakespeare will have known it. Holinshed doesn’t specify reds, but this will have been understood: in the logistics of war, reds were lighter (no brine) and easier to distribute. Audiences would have been as familiar with the Battle of the Herrings, as they were with previous Oldcastle characterisations and his promotion as a Protestant saint in Foxe’s Book of Martyrs (1563).

Shakespeare hadn’t used Fastolf in Henry VI, Pt 1, which he wrote 1591, possibly in collaboration with Marlowe and/or Nashe. So, here he was, the great protector of red herrings, now able to protect the honour of the Lord Chamberlain and his ancestor who’d been hanged like a red herring in a smokehouse.

Fastolf, commended for bravery at the Battle of the Herrings, was accused of cowardice just four months later at the English military disaster that was the Battle of Patay. Joan of Arc, one of whose famous visions was of the Battle of the Herrings, told the Dauphin he was going to win at Patay. Her historical involvement may have offered a smoky, stake-burning resonance to the red herring gag.

The charge of cowardice was unjustified (Fastolf left the field of battle only after the English cavalry had fled) but it stuck. In the earliest published text for Henry IV, Pt 1 (already Falstaff-ed in 1598) the old rogue discusses cowardice, hanging and herrings:

Go thy ways, old Jack; die when thou wilt. If manhood, good manhood, be not forgot upon the face of the earth, then am I a shotten herring. There live not three good men unhanged in England, and one of them is fat and grows old: God help the while! A bad world, I say. I would I were a weaver; I could sing psalms or anything. A plague of all cowards, I say still.

[Shotten herrings are spents – lean and lacking in oil after spawning.]

THIS IS NOT THE MAN

The date of Henry IV, Pt 1‘s second run is uncertain. William Brooke died in March 1597, so he may or may not have been able to chuckle at Shakespeare’s wit. Falstaff was a hit, however. Premiered a month after Brooke died, The Merry Wives of Windsor has Master Ford respond to the big man’s cuckolding attempts by putting on a disguise and calling himself Brooke (changed to Broome in the 1623 Folio text). With George Carey now appointed Lord Chamberlain, it was one of the earliest productions by the reborn Lord Chamberlain’s Men.

In an Epilogue to Henry IV, Pt 2, written in 1597/98, Shakespeare promises more appearances for his great comic creation:

If you be not too much cloyed with fat meat, our humble author will continue the story, with Sir John in it, and make you merry with fair Katherine of France, where, for anything I know, Falstaff shall die of a sweat, unless already he be killed with your hard opinions; for Oldcastle died martyr, and this is not the man.

Quite apart from anything else, the epilogue demonstrates how well the Falstaff/Oldcastle joke had played. In the forthcoming Henry V, Falstaff would die of a sweat (rather than a red herring roasting). In the event he doesn’t even appear and, reporting his death, the Hostess goes out of her way to describe how his feet, knees and so upward were as cold as any stone.

It’s quite possible Shakespeare felt Hal’s I know thee not, old man at the end of Henry IV, Pt 2 had already done the job. For my money, however, Henry V, written in 1599,has always been a slightly disappointing end to an otherwise great historical trilogy. It lacks Falstaff. His character couldn’t, of course, have delivered Oldcastle’s trial, rebellion or fate, but Shakespeare might also have become concerned at growing evidence of political impatience with the creative sector. He was always one to play fast and loose with history, but he was astute. As Falstaff himself says, the better part of valour is discretion.

CRITICAL ANALYSIS

The Brooke-demanded change of name is well known. The Fastolf/Falstaff equivalence is accepted. There may be Shakespearean critical discussion of the Battle of the Herrings, but, apart from a herripedia entry, it doesn’t immediately reveal itself in internet searches. Without it, of course, there is no red herring gag at this stage, but in the light of Jonson’s and Nashe’s usages and Shakespeare’s intimate knowledge of Hollinshed’s Chronicles, it’s hard to see him having missed it. Without the red herring joke there was also no need for the epilogue’s conciliatory, Oldcastle died martyr.

Anatomy of a Joke, Pt 2: Jonson

Jonson and Nashe’s use of the joke came after William Brooke’s death, but they both retargeted it on his son, Henry Brooke. He seems to have given them good cause. Shakespeare doesn’t pun on the Cobham name (he’d been specifically warned, after all) but both Jonson and Nashe do. The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary registers doubt as to whether cob meant a young herring, but Jonson’s and Nashe’s use of it, in a joke the dictionary editors may not fully have appreciated, suggests that it did. The dictionary acknowledges it as meaning a red herring’s head, whereas Nashe seems to expand this to what is left of a red herring when it has been filleted. It was also used for a wealthy man, particularly one who was a bit full of himself.

THE ISLE OF DOGS

In the summer of 1597 Jonson and Nashe collaborated on The Isle of Dogs, a lost satirical play. We’ll never know for certain what upset the authorities – or who in particular the satire targeted – but it was condemned as slanderous, lewd and seditious by the Privy Council (led by Henry Brooke’s brother-in-law, Robert Cecil).

In A Cup of News: The Life of Thomas Nashe (1984) Charles Nicholl speculates that, set on the Isle of Dogs,a marshy Thames peninsula hangout of ne’er-do-wells, the play might have metaphorically suggested a corrupt state. It may also have satirised the disastrousIslands Voyage, led by the Earl of Essex and Sir Walter Raleigh, which at that time had taken the English fleet away when a third Armada threatened. There was famine in the land and unrest, which together with the Spanish threat may have heightened concern at any pot stirring. Nicholl suggests Henry Brooke was at least one its targets and he was in the Raleigh circle.

London’s theatres were ordered to be closed, although this might have been separately because of the plague, The Isle of Dogs, however, was very specifically banned. As well as sharing writing credits, Ben Jonson was one of the actors and was briefly imprisoned with fellow cast members Gabriel Spencer and Robert Shaa. The Privy Council put its top man Richard Topcliffe on the interrogations. Jonson claimed his judges could gett nothing out of him to all their demands but I and No. He also claimed informers were placed in the prison to catch advantage of him.

Later Jonson wrote Epigram LIX on spies:

SPIES, you are lights in state, but of base stuff,

When you’ve burnt yourselves down to the snuff,

Stink, and you are thrown away. End fair enough.

His Epigram CI, Inviting a Friend to Supper includes the lines:

And we will have no Pooly or Parrot by;

Nor shall our cups make anie guiltie men.

Parrot and Robert Poley were known informers, Poley one of the murky figures providing witness statements when Christopher Marlowe died (apparently in a tavern brawl). They were probably the informers Topcliffe had used. The Isle of Dogs was seen to be a serious affair.

EVERY MAN IN HIS HUMOUR

Jonson was released in October, but imprisoned again early the following year, this time for the killing Gabriel Spenser in a duel. He was released again and in 1598 had his first big success as a playwright with The Lord Chamberlain’s men: Every Man in his Humour. Shakespeare probably played the part of the old gentleman, Knowell; the story goes he’d persuaded a reluctant company into taking the play on.

Jonson’s use of the joke is the most direct. The play has a comic character called Cob, a water-bearer (generally acknowledged to be a reference to the Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports). In Act 1, Scene 3, he claims:

Mine ance’try came from a king’s belly, no worse man; and yet no man either, by your worship’s leave, I did lie in that, but herring, the king of fish (from his belly I proceed), one of the monarchs of the world, I assure you. The first red herring that was broiled in Adam and Eve’s kitchen, do I fetch my pedigree from, by the harrot’s [herald’s] book. His cob was my great, great, mighty great grandfather.

In Act 3, Cob, complaining of his herring family fortunes, takes on fasting days – I would we had these ember weeks and these villainous Fridays burnt. Abstinence from meat during Lent, Ember Days and all Fridays was a Roman Catholic ordinance. With the Reformation, fasting requirements went and this was popular. Englishmen grew increasingly belligerent about their inalienable right to beef. Fasting, throughout much of Europe, meant herring – in Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s The Fight Between Carnival and Lent (1559) Lent goes into battle with two herrings on a paddle. Fasting came back with Queen Mary and went again with Elizabeth.

English Protestantism’s militant rejection of the fast threatened the home market for fishing communities. Quite apart from any envious glances at the Dutch Republic with its stated belief in the herring fishery as the principal gold-mine to its inhabitants, England (and Scotland) looked to the projected Dutch model of a naval empire underpinned by its fishing fleet as an essential maritime training ground. Elizabeth re-established fasting by introducing secular Fish Days.

Jonson’s Cob cries out on behalf of his sacrificed family:

A fasting-day no sooner comes, but my lineage goes to wrack; poor cobs! they smoak for it, they are made martyrs o’ the gridiron, they melt in passion: and your maids do know this, and yet would have me turn Hannibal, and eat my own flesh and blood. My princely coz, [he pulls out a red herring] fear nothing; I have not the heart to devour you, an I might be made as rich as king Cophetua. O that I had room for my tears, I could weep salt-water enough now to preserve the lives of ten thousand thousand of my kin!

The audience of the Lord Chamberlain’s Men already knew the red herring joke and liked it. Cheap laughs are good laughs. Groans of recognition are also great. Meanwhile, Jonson could be seen (as a very recent convert) pointing things away from England’s Catholics towards the anti-fasters and the role Puritanism might be playing in social unrest.

There are later Jonson references to bloat or red herrings in masques created for James I court – Mercury Vindicated from the Alchemists (1616)and Masque of Augurs (1622). There’s also one in John Fletcher’s The Island Princess (1619). These may or may not have been seen as references to the old joke.

Anatomy of a Joke, Pt 3: Nashe

Nashes Lenten Stuffe (1599) is, as said, the greatest herring work in English literature, but he and it need a bit of introduction. It is textually evasive and without the reference points Nashe’s contemporary audience might have had, readers can lose their way. Nothing in what was to be his last work can be taken at face value. In the constant multiplication of meanings, the whole text is the joke and, through it, much more besides. Endlessly inventive, it is a tour-de-force.

NASHE’S RED HERRINGS

With its pastiche, linguistic invention, puns and ambiguities Lenten Stuffe looks forward to the Ulysses and Finnegans Wake of James Joyce. Nashe is certainly a forerunner of Lewis Carroll’s Humpty Dumpty in Through the Looking Glass:

‘When I use a word,’ Humpty Dumpty said in rather a scornful tone, ‘it means just what I choose it to mean – neither more nor less.’

‘The question is,’ said Alice, ‘whether you can make words mean so many different things.’

‘The question is,’ said Humpty Dumpty, ‘which is to be master – that’s all.’

Nashe annoyed and was admired for the wild energy and defiance of his wit. You never know where he’s going to take you next. Each red herring reels in and plays with a Cobham at the end of a line – Nashe even includes the story of a practical joke in which a angler pretends to catch a red herring in the River Cam. In playing with his enemy, however, he conjures up something greater. Towards the end of his text, there’s a list of its other uses, including, to draw on hounds to a sent, to a redde herring skinne there is nothing comparable.

Ironically enough, some claim Cobbett’s Rural Rides (1822) provided the first use of red herring to mean a false trail. Nashes Lenten Stuffe is a forest of false trails or, alternatively, a whole shoal of red herrings. It is the first and, by a long mile, the most extraordinary demonstration of its figurative sense.

Wit was culturally important to the Elizabethan writers and audiences. Nashe’s readers would have followed his trail of hints and suggestions like breadcrumbs, but their starting point will have been the joke, which was out there and which is, out of all the endless red herring possibilities, the one which isn’t directly presented in the text. Following the herrings is, nevertheless, the most effective way of reading the work.

The Isle of Dogs had shown the dangers of stepping over the line. Like a Soviet dissident teasing the Politburo, Nashe was also writing a text, any perceived interpretation of which was deniable: he claims the right to be master of his own words and meanings.

THE ARGUMENTARIAN

Shaggy-haired with a gag-tooth, Nashe was boyish-looking, skinny and verbally combative. He seems to have had that electrifying capacity for sustained comic extemporisation; a manic and, maybe at times, scary ability to make endless connection between things plucked out of the air. After he died, the anonymous friend/admirer who wrote the Cambridge Parnassus Plays wrote:

Some things he might have mended, so may all.

Yet this I say, that for a mother witt,

Few men have ever seene the like of it.

Nashe had a degree from Cambridge and placed high value on his demonstrable learning. In Shakespeare’s Love’s Labours Lost (1594/5), Moth, argumentatively witty servant to Don Armado, is an affectionate portrait of him. His friend and mentor Robert Greene, an elder statesman in both theatre and pamphleteering, had coined the description of him as young Juvenall, that byting Satyrist. Armado calls Moth a juvenal three times: more than enough for Elizabethan audiences to get the reference.

In Strange News (1593) Nashe had directed his biting satire at Gabriel Harvey, a writer and Cambridge academic who’d mocked Greene’s death in Four Letters and Certain Sonnets (1592). Harvey came back with Pierces Supererogation or a New Prayse of the Old Asse (1593) – Piers Pennilesse, His Supplication to the Divell (1592) was Nashe’s most popular work. In the middle of the exchange, Nashe seems to have gone through a crisis of faith and he actually apologised to Harvey in Christs Teares over Jerusalem (1593), but Harvey came back that same year with a New Letter of Notable Contents.

Nashe didn’t reply a while. His own explanation was that bitter-sauced invectives didn’t pay the rent, although Nicholls speculates he might have been suffering from depression. Harvey was asking for it, however, and he got it when Nashe eventually returned to the fray with the devastating Have With You To Saffron-Walden, Or, Gabriell Harveys hunt is up (1596).

Greene, who also coined upstart crow for Shakespeare, was possibly the larger than life figure upon whom Shakespeare based the character of his Oldcastle/Falstaff. Meanwhile, Charles Nicholl suggests Moth’s master, the pompous Armado, is a caricature of Harvey: servant and master, wit and pomposity, archetypally locked together like some punishment in the outer circles of Hell.

Harvey didn’t reply to Have with You to Saffron-Walden, but, capitalising on Nashe’s difficulties after The Isle of Dogs, Richard Lichfield, barber surgeon of Cambridge, took up arms on Harvey’s behalf with The Trimming of Thomas Nashe gentleman (1597).

LENTEN STUFFE

After the closing down of The Isle of Dogs, Nashe had managed to get out of London before he could be arrested, but his books and papers were seized, suggesting he’d left in a hurry. It’s possible he was warned: George Carey and Henry Brooke weren’t best pals. Carey had wanted the post of Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports, which Brooke inherited from his father.

With Jonson released within three months, Nashe may have felt the political uproar was dying down: he eventually surfaced in Great Yarmouth in late November or December. We only have his account, so he may still not have been making himself all that visible. In the text, itself, he claims to have written most of Lenten Stuffe during the following Lent, which he says accounts for the title.

On the title page, he promises The Description and first Procreation and Increase of the towne of Great Yarmouth in Norfolke, followed by a new Play never played before, of the praise of the Red Herring. And this is what he gives us. The text breaks into four sections: the Epistle Dedicatorie; the preface; the description and history of Great Yarmouth (principall Metropolis of the redde Fish); and a satirico-fantastical improvisation upon the red herring.

DEDICATION AND PREFACE

The Epistle Dedicatorie to Nashe’s celebration of a smoked herring is To his worthie good patron, Humphrey King, Lusty Humfrey… little Numps… King of the Tobacconists. In the C16th a tobacconist was not a seller but a smoker (Jonson also plays with tobacco and fish smoking in Every Man in his Humour). The dedication is a portrait of a sometime poet and poet’s friend, a man who enjoys lowlife good times and is generous with money he may actually owe to tradesmen.

The preface is To his Readers, hee cares not what they be:

Nashes Lentenstuffe: and why Nashes Lentenstuffe? some scabbed scald squire replies, because I had money lent me at Yarmouth, and I pay them againe in prayse of their towne and the redde herring: and if it were so, goodman Pig-wiggen, were not that honest dealing? pay thou al thy debtes, so if thou canst for thy life: but thou art a Ninnihammer; that is not it; therefore, Nickneacave, I call it Nashes Lenten-stuffe, as well for it was most of my study the last Lent, as that we use so to term any fish that takes salt, of which the Red Herring is the aptest.

Nashe, like his Piers Pennilesse alter ego, often lacked the means to pay his debts. He’d spent time in debtors’ prison. Now unable even to earn the most modest of crusts from his writing, Lenten Stuffe is Nashe on hard times; red herring a kind of whale meat again.It’s also a nod and a wink to Falstaff and his wagon train of lenten provisions, to Shakespeare and the origin of the joke. At the end of the preface, however, he sets out his stall:

Every man can say Bee to a Battledore, and write in prayse of Vertue and the seven Liberall Sciences, thresh corne out of the full sheaves and fetch water out of the Thames; but out of drie stubble to make an after harvest, and a plentifull croppe without sowing, and wring juice out of a flint, that’s Pierce a Gods name, and the right tricke of a workman. Let me speake to you about my huge woords which I use in this booke, and then you are your own men to do what you list. Know it is my true vaine to be tragicus Orator, and of all stiles I most affect & strive to imitate Aretines, not caring for this demure soft mediocre genus, that is like water and wine mixt together; but give me pure wine of it self, & that begets good bloud, and heates the brain thorowly: I had as lieve have no sunne, as have it shine faintly, no fire, as smothering fire of small coales, no cloathes, rather than weare linsey wolsey.

Italian satirist Pietro Aretino (1492 – 1556) was the scourge of princes. He’d famously written The Last Will and Testament of the Elephant Hanno, which had taken the death of the Pope’s pet as an opportunity to mock the good and great of Rome from Leo X down.

YARMOUTH

Nashe titles his text proper, The Praise Of the red herring. Opening with a lament for the straunge turning of the Ile of Dogs from a commedie to a tragedie, he talks of how:

The silliest millers thombe or contemptible stickle-banck of my enemies is as busie nibbling about my fame as if I were a deade man throwne amongst them to feede upon.

A young herring, the head or filleted remains of a red herring and a wealthy git, a cob was also a miller’s thumb or European bullhead: a small freshwater fish. Suggesting the red herring joke without mentioning it, Nashe accuses the young Cobham, Henry Brooke, of having at least fanned the Isle of Dogs flames. He tells us he is going to deal with Lichfield in a subsequent pamphlet, a forthcoming answere to the Trim Tram,which will make you laugh your hearts out.

Poor, hungry and feeling unfairly unloved, he translates a Latin epigram by the Scottish poet George Buchanan (1506 – 1582):

Seaven citties stroave whence Homer first shoulde come;

When living, he no country had nor home.

Value writers while they’re alive, Nashe-via-Buchanan says and, by the way, what am I supposed to live on, here? He then adds I am no Tiresias or Calchas to prophecie, but yet I cannot tell, there may bee more resounding bel-metall in my pen then I am aware, and if there bee, the first peale of it is Yarmouthes. It’s mock heroic bravado, denial of responsibility and provincial bathos all rolled into one. Buchanan, however, had been a tutor to the young James Stuart, the leading contender for the succession. However mock heroic, there is threat in the resounding bel-metall: Nashe may be suggesting the possession of information or a connection, which he might play with later in the text.

After his preamble he comes, at last, to his promised account of Great Yarmouth, its geography, history and fishery. Throughout his works, but especially here, Nashe had an instinct for journalistic research. He happily lifts material from any available sources, but adds direct observation – and always makes any borrowings comically his own.

Fortunately, the history of Yarmouth offers plenty of scope for him to play with Brooke. The town had struggled for a long time throwing off the yoke of the Barons of the Cinque Ports. The Normans had put them in charge of the all-important Herring Fair. Bribing kings was always been the best way to change royal policy, but sometimes there were more direct conflicts. Nashe notes, in 1240 AD:

In a sea battle the ships and men [of Yarmouth] conflicted the Cinque Ports, and therein so laid about them that they burnt, took, and spoiled most of them, whereof such of them as were sure flights (saving a reverence of their manhoods) ran crying and complaining to King Henry the Second, who, with the advice of his council, set a fine of a thousand pound on the Yarmouth men’s heads for that offence, which fine in the tenth of his reign he dispensed with and pardoned.

In Red Herrings and the ‘Stench of Fish’ (2014) Kristen Abbott Bennett suggests this is a subversive comment on arbitrary power. Coming from Nashe, born in Yarmouth’s rival town of Lowestoft, she suggests it is also a critique of privileges arbitrarily given to Yarmouth, which were damaging to its competitors. This is entirely plausible, although his father, a Lowestoft curate, had moved with his family to an inland Norfolk rectory when Nashe was 6, so it probably shouldn’t be overplayed. It can also be seen (at one and the same time) as suggesting historical precedents for pardons in the matter of, say, red herring struggles with a Cinque Ports Lord Warden.

Not that he’d ever want to labour the point:

I had a crotchet in my head, here to have given the raines to my pen, and run astray thorowhout all the coast towns of England, digging up their dilapidations, and raking out of the dust-heape or charnell house of tenebrous eld the rottenest relique of their monuments, and bright scoured the canker eaten brass of their first bricklayers and founders, & commented and paralogized on their condition in the present, & in the pretertense; not for any love or hatred I bear them, but that I would not be snibd, or have it cast in my dishe that therefore I prayse Yarmouth so rantantingly because I never elsewhere bayted my horse, or took my bowe and arrows and went to bed.

A few pages later, however, almost as an afterthought, he helpfully points out:

Rye is one of the antient townes belonging to the cinque ports, yet limpeth cinque ace behinde Yarmouth, and it wil sincke when Yarmouth riseth, and yet, if it were put in the balance against Yarmouth, it would rise when Yarmouth sincketh, and to stande threshing no longer about it, Rye is Rye and no more but Rye, and Yarmouth wheate compared with it.

When all is said and done, what is it Lord Wardens do?

THE HERRING FISHERIES

While in Yarmouth, Nashe spent time with fishermen. He seems to have enjoyed their company and to have been sympathetic to their concerns. He probably already knew of the herring’s notorious unreliability. The shoals can abandon customary fishing grounds for years at a time. Seen inevitably as a punishment from God, it was usually for the licentiousness of herring fairs.

Turning the red herring Brooke attack on its head, Nashe claims the fish as a legate of peace, abhorring conflict. Plentiful shoals off Scotland, he writes, disappeared when, after Robert the Bruce had sent his deare heart to the haly land, for reason he caud not gang thider … a foule ill feud arose his amongst his sectaries and servitours, and there was mickle tule…

He had a great ear, employing a convincing cod Scots to tell his tale within a tale. He then tells us, This language or parley have I usurpt from some of the deftest lads in all Edenborough towne. This could be taken to suggest he’d been in Edinburgh, quite possibly after his escape from London, and that, while there, he’d been actively researching the herring. Rather than just repaying a debt after the event, he’d come to Yarmouth because it was the production capital of the red herring.

Whether he’d been in Edinburgh or not, together with the George Buchanan reference, it can be seen as hinting Stuart connections. In the febrile context of English concerns around the succession, it’s hard not to imagine a fair amount of ‘reaching out’ across the border. Nashe would have been a natural as an intelligence gatherer for one of his patrons.

It has to be said, the Stuarts were also herring mad – far more so than the Tudors, Plantagenets or Normans had ever been. James V of Scotland (James VI & I’s grandfather) had gone to war with the Holy Roman Empire over the Dutch fishing of his coastal waters. The Dutch had the gall to claim the herring shoals of their Groote Visserye or Grand Fishery, which ran down Britain’s Coast from Shetland to the Channel, underpinned their economic miracle. With the succession, unification of Scottish and English herring fisheries was a key Stuart economic strategy.

Growing out of his hunger, Nashe’s Lenten Stuffe could be seen as a bid for favour with the incoming administration: a dainty dish to set before the new king; a play upon England’s quintessential herring product.

LET THE PLAY BEGIN

Nashe’s account of Yarmouth provides the base from which an exploration of its red herring trade takes off and, with it, his imagination.

The poets were triviall, that set up Helens face for such a top-gallant Summer May-pole for men to gaze at … As loude a ringing miracle as the attractive melting eye of that strumpet can we supply them with of our dappert Piemont Huldrick Herring, which draweth more barkes to Yarmouth bay, then her beautie did to Troy.

The Brookes are there in every reference to herrings, hangings, fires and smokings, but Nashe will roast them through praise. If they be Puritan, let them be heroes of English Protestantism: to thinke on a red Herring, such a hot stirring meate it is, is enough to make the cravenest dastard proclaime fire and sword against Spaine.

At the same time, if anyone thought he was making a joke about a Protestant heretic martyr and his descendants, he can just as easily shift to the saints of Shi’a Islam. Free-associating his way from the Ottoman red herring trade and the Turkish habit of hanging men from hooks (had they first learnd it of our Herring men or our herringmen of them?) he demonstrates that the true etimologie of Imam Ali (Mortus Alli) was nothing more than mortuum halec, a dead red herring, and no other, though, by corruption of speech, they false dialect and misse-sound it. (In Medieval Latin halec is herring). Then again, it could be a saint of Roman Catholicism or it could have come down from the gods on Mount Olympus.

Few people know about red herring, these days. There isn’t a single standard: variations in salting and smoking produce different colours, creating sub-categories under the broad ‘red’ banner. When I visited HS Fish of Great Yarmouth in the late 1990s, the company produced red herring for the Caribbean and West African markets, silver herring for the Italian market and golden herring for Greece and Egypt. The red herring trade with the Ottoman empire was strong in Nashe’s time. His verbal play suggests that the golden variety was already established there as the preferred commodity.

Nashe plays on red herrings as guilded. Kristen Abbott Bennett sees a reference to Yarmouth’s powerful Fishermen’s Guild, its privileges and arbitrary economic power. This is definitely one strand of ambiguity. On the surface, Nashe uses it to mean gilded, almost certainly referring to both golden herring and the guilders of export income.

England and Scotland had poor reputations for salt herring: their outputs sold to the cheap end of the European market; England’s red herring, however, was internationally a valued product. Even more importantly for Nashe, golden herring enabled him to exploit the heartlands of classical mythology. A plaine golden coated red herring becomes a partner in Jupiter’s slippery pranckes.

When the stories talk of Jupiter rayning himself downe in golde into a womans lappe (Danaë, who then gave birth to Perseus), he had, of course, actually transformed himself into a red herring (so much more practically phallic). In fact, in any of his golden manifestations, Jupiter was a red or guilded herring. And when mankind first saw one, (having never beheld a beast of that hue before) the red herring was in their temples inshrined for a God. As for Midas eating gold, he was, of course, just eating a red herring. Unfamiliar with it, because at the time these hard-smoked fish were still the delicates of the gods, it naturally gave him a bit of indigestion.

HERO AND LEANDER

There are four extended herring narratives or fancies in Lenten Stuffe. The first, coming out of this classical foreplay, is a comic retelling of his late friend’s unfinished poem:

Let me see, hath any bodie in Yarmouth heard of Leander and Hero, of whom divine Musaeus sung, and a diviner Muse than him, Kit Marlow?

Musaeus Grammaticus had written the original in the C6th AD; Marlowe’s Hero and Leander was published posthumously in 1598, but Nashe probably read it in manuscript.

Hero is the beautiful virgin, looked after by an old nurse and raised to serve at the altar of Venus in Abidos (on the Asian side of the Hellespont). Leander is the handsome young man from Sestos (on the European side). These two towns like Yarmouth and Leystoffe were stil at wrig wrag, & suckt from their mothers teates serpentine hatred one against each other, but (as in Romeo and Juliet) the two young people fall in love. Leander swims across the Hellespont to be with Hero. A storm rages, but still he won’t be put off. He drowns in the salt sea; she finds his body, washed ashore and bathes it in her salt tears.

Lesser poets finished what Marlowe couldn’t, but Nashe’s version, played for laughs, is by far the best. Going beyond them all and taking his cue from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, he has the gods take pity on the couple, transforming Hero into a herring – Her(o)-ing – and Leander into a ling (it begins with L; it might be a little early for a play on the Sanskrit-derived lingam, but ling is a phallic-enough fish, anyway). The tears of the gods are such, they also decide to turn Nursey into a mustard plant (because mustard brings tears to your eyes). And from that day to this, as Nashe points out, whenever ling and herring are brought to the table, mustard is their essential companion.

However similar to Sestos and Abidos in their wranglings, Yarmouth or Lowestoft are, of course, a long way away, but:

Loving Hero, how ever altered, had a smack of love stil, & therefore to the coast of loving-land (to Yarmouth neere adjoyning, & within the liberties of Kirtley roade) she accustomed to come in pilgrimage every yeare, but contentions arising there, and shee remembering the event of the contentions betwixt Sestos and Abidos, that wrought both Leanders death and hers, shunneth it off late, and retireth more northwards…

Lovingland (by the village of Herringfleet) is 9 miles south west of Yarmouth; Lowestoft is 10 or so miles due south.

THE KING OF FISHES

Nashe switches to his second extended fancy with the remarkably economical, Whippet, turne to a new lesson (or another trail). It tells of how the herring came to be the King of Fishes.

A falcon, escaped at sea from its falconer and, diving for a flying fish, ends up in the jaws of a shark. The birds declare war on the fish, before realising their reliance on web-footed ducks to carry them into battle. The ducks, of course, were never going to trust hawks on their backs, so it all comes to nothing. In the threat of war, however, the fish feel the need of a king to lead them into battle, but don’t trust any of the obvious candidates – No ravening fish they would putte in armes, for feare after he had everted their foes, and flesht himselfe in bloud, for interchange of diet, hee would raven up them.

So, None wonne the day in this but the Herring, which is why, ever since that time, the herring hath gone with an army. Up until the C19th, the word herring was thought to derive from the Germanic root word heer or army.

Is it stretching things to place this fable in the context of the imminent succession? And where might Brooke be fingered? There may be answers to these questions (see later), but there was also a simple narrative requirement for the herring to become King of Fishes before Nashe’s third fancy: the origin of the red herring and how it came to be a saint.

FISHERMAN AND POPE

All popes are the successors of St Peter, who was a fisherman. Jesus enjoined his apostles to become fishers of men. Given the way Nashe’s mind works, however blasphemous, by this time in the text, with its divinity established, it’s hard not to think of our red herring in the light of the Christian fish symbol, derived from the Greek acronym IChThYS or Iesous Christos Theou Yios Soter (Jesus Christ, Son of God, Saviour).

Nashe’s pope is Vigilius. Before we get to Rome, however, the first red herring is accidentally smoked on Cerdic Sands, which Nashe pictures as an Ur-Yarmouth. In 495 AD, Cerdic the Saxon may or may not have first landed on a sandbank in Norfolk (some say he jumped ashore in Hampshire) but Yarmouth tradition (and Nashe had been shown Manship’s History of Great Yarmouth in manuscript) dates the rise of its herring fishery to shortly after his landing. This was particularly important for Yarmouth (and might have been in any bid for royal favour) because England’s monarchy draws its bloodline from Cerdic (who drew his directly from Woden).

It is to be read, or bee heard of, howe in the Punieship of nonage [early days] of Cerdicke sandes, when the best houses and walles there were of mudde or canvase, or Poldavies entiltments [rough canvas lean-tos] a Fisherman of Yarmouth having drawne so many herrings hee wist not what to do withall, hung the residue that he could not sel nor spend, in the sooty roofe of his shad a drying…

The weather was colde, and good fires he kept and what with his fiering and smoking, or smokie firing, in that his narrow lobby, his herrings, which were as white as whales bone when hee hung them up, now lookt as red as a lobster. It was foure or five dayes before either hee or his wife espied it, & when they espied it, they fell downe on their knees & blessed themselvs, & cride, a miracle, a miracle, & with the proclaiming it among their neighbours they could not be content, but to court the fisherman would, and present it to the King, then lying at Borrough Castle two miles off.

Nashe casts this third fancy as folk tale, set at a time, as he’s already established in his history, when Yarmouth was little more than a sandbank. Vigilius was Pope from 537 to 555 AD. Nashe has allowed a few decades for a fishing settlement to be established after Cerdic, but it’s well before the settlement is fully established. For a story as outrageously scurrilous as the one Nashe is telling, it’s interesting that he takes the trouble to establish historical plausibility.

Having sold his miraculous red herrings throughout England, the fisherman takes them to Rome. He’s robbed on the way and only has three left when he arrives in the Holy City and cries his wares in the market place. Casting a licourous glaunce,Pope Vigilius’ caterer asks what he’s selling.

The king of fishes, hee answered: the king of fishes? replied hee, what is the price of him? A hundred duckats, he tolde him: a hundred duckats? quoth the Popes caterer, that is a kingly price indeede, it is for no private man to deale with him: then hee is for mee, sayde the Fisherman, and so unsheathed his cuttle-bong, and from the nape of the necke to the taile dismembred him and pauncht him up at a mouthfull.

The caterer goes back and tells Vigilius. Is it the king of fishes? exclaims the Pope, and is any man to have him but I that am king of kings, and lord of lords? Go, give him his price, I commaund thee. The caterer goes back but hesitates because the price has gone up to two hundred ducats, so the fisherman eats the second one. The Pope, so in his mulliegrums, curses the caterer with bell, book & candle and sends him back. The caterer has to pay three hundred ducats, but finally gets his red herring.

So far, so good: England’s red herring has got the better of Rome and all the Pope’s cooks gather to bring the King of Fishes to the kitchen. It is, of course, the martyred Oldcastle, but Nashe was just getting going.

The clarke of the kitchin … would admit none but him selfe to have the scorching and the carbonadoing of it, and he kissed his hand thrice, and made many Humblessos, ere he woulde finger it: and such obeysances performed, he drest it as he was enjoyned, kneeling on his knes, and mumbling away twenty ave Maryes to himselfe in the sacrifizing of it on the coales, that his diligent service in the broyling and combustion of it, both to his kingship and to his fatherhood, might not seem unmeritorious. The fire had not perst it, but it being a sweaty loggerhead greasie sowter, endungeoned in his pocket a twelvemonth, stunk so over the popes pallace, that not a scullion but cryed foh, and those which at the first flocked fastest about it now fled the most from it, and sought to rid theyr hands of it than before they sought to blesse theyr handes of it. Wyth much stopping of theyr noses, between two dishes they stued it, and served it up. It was not come wythin three chambers of the Pope, but he smelt it, and upon the smelling of it enquiring what it should be that sent forth such a puissant perfume, the standers by declared that it was the king of fishes: I conceyted no lesse, sayde the Pope, for lesse than a king he could not be, that had so strong a sent, and if his breath be strong, what is he hymself? like a great king, like a strong king, I will use him; let him be caried backe, I say, and my Cardinalls shall fetch hym in with dirge and processions under my canopy.

Jonson had referred to the gridiron, but with Nashe the kitchen martyrdom becomes visceral comedy.

The whole Colledge of scarlet Cardinalles, with theyr crosiers, theyr censors, their hosts, their Agnus deies and crucifixes, flocked togither in heapes as it had beene to the conclave or a general counsaile, and the senior Cardinall that stood next in election to bee Pope, heaved him up from the Dresser, with a dirge of De profundis natus est fex; rex he should have sayd, and so have made true latine, but the spirable odor and pestilent steame ascending from it put him out of his bias of congruity.

The smell is so bad, the Pope flees the Vatican. The traumatised cardinals create a necromantic chalk circle to summon up the spirit of this mighty king, but the red herring has nothing to say to them. Running to Vigilius, they craved that this king of fishes might first have Christian buriall, next, that hee might have masses sung for him, and last, that for a saint hee would canonize him.

Which Vigilius does. And if you don’t believe the tale, Nashe suggests:

Looke to the Almanack in the beginning of April, and see if you can finde out such a saint as saint Gildarde; which in honour of this guilded fish the Pope so ensainted: nor there hee rested and stopt, but in mitigation of the very embers wheron he was sindged (that after he was taken of them, fumed most fulsomely of his fatty droppings,) hee ordained ember weekes in their memory, to be fasted everlastingly.

A legate of peace stinks to High Heaven; a proto-Protestant martyr is canonised by a Pope (a pope, incidentally, who was declared a heretic by Emperor Justinian; a saint, of course, who doesn’t appear in any almanac).

THE RELUCTANT TURBOT

With Nashe’s third fancy already having provided the comic climax to Lenten Stuffe and quite naturally leading into its mock heroicending, the fourth fancy is curious. There are two stories he could tell, he says, but he only gives us one. For a preamble, he launches an attack on those false-interpreters who:

Out of some discourses of mine, which were a mingle mangle cum putre, and I knew not what to make of my selfe, have fisht out such a deepe politique state meaning as if I had al the secrets of court or common-wealth at my fingers endes.

A satirist’s protestations of innocence are always a bit like a schoolboy’s Who? Me? Nashe’s suggest disguise at the very least: that he maybe does have some secrets at his finger ends. For the first time in the text, the red herring becomes an active player, a character, but far from the hero projected elsewhere in Nashe’s praise, he is revealed as deeply unpleasant.

There was a Herring, or there was not, for it was but a cropshin, one of the refuse sort of herrings, and this herring, or this cropshin, was sensed and thurified in the smoake…

A shotten herring, but carrying over the incense-laden canonisation of the third fancy, he is simultaneously a Triton of his time, and a sweet singing calandar to the state, yet not beloved of the shoury Pleyades or the Colossus of the sunne. As the red herring, he’s obviously Henry Brooke, who as Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports could also be seen as a Triton or sea god. At the same time there’s a hint of Brooke’s friend, the out-of-favour Sir Walter Raleigh: Nashe’s red herring is an Adelantado; the Adalantado was admiral of the Spanish fleet, against which the Essex-Raleigh Islands Voyage had so notably failed.

Nashe gives us the tale of a red herring who goes a-wooing Lady Turbot. She’ll have none of him; he in an olympick rage accuses her of a violent rape of his heart; she’s tried, found guilty and sentenced to be boyled to death in hot scalding water and to have her posterity thoroughly sawst and sowst and pickled in barelles of brinish teares. Even for Nashe it’s savage: it’s hard not to feel pity at the cruel consequences of a red herring’s unwanted advances.

Without being exactly clear, it takes the form of direct political allegory – more so, at least, than the constantly shifting ground elsewhere in Lenten Stuffe.

SPURIOUSER AND SPURIOUSER

Three meanings suggest themselves and Nashe could, as always, have been playing with all of them simultaneously.

1. Leander became a Ling; the Turbot could be Thomas himself. The feud with Brooke is flipped into a reluctant courtship and Nashe, not playing ball with the Privy Council’s desire for an end to inconvenient hostilities, ends up in the soup.

2. Henry Brooke was actually a-wooing around this time. The Queen’s Maid of Honour, Margaret Radcliffe was responsive to his charms, but, in what might be read as insincerity, he was also flirting with her best friend’s sister, Elizabeth Russell and the recently widowed Lady Frances Howard, Countess of Kildare (who he actually married in 1601). Not that Nashe could be referring to it, but in August 1599 Margaret Radcliffe, mourning the deaths of her brothers and upset at betrayal, shut herself in her chamber for four days. She died in the November, having refused to eat. Jonson wrote an acrostic epigram (XL) on her death, suggesting London’s literary scene had a clear sense of her and her story at the time.

3. If we take Brooke and Raleigh together, it becomes more speculative, but it’s quite possible Nashe had picked up something of their first steps into the dangerous waters of the succession-focused Main Plot – even though he didn’t live to see its endgame, which came in 1603. With James VI & I’s mum, Mary, Queen of Scots, executed in 1587, he was in the frame for the England job, but his cousin, Arbella Stuart was another contender. It’s tempting to see Lady Turbot’s resistance as Arbella’s noted reluctance to encourage approaches on the subject of the succession. Even so early on, Nashe might have seen the approach itself as likely enough to condemn her. Turbot/Stuart isn’t an impossible leap.

THE MAIN PLOT

The Main Plot got its name because of a linked Bye Plot (for his part in which Henry Brooke’s brother George was executed). The plots grew out of an alliance of convenience between Puritans and Catholics aimed at securing religious tolerance for both. The Bye Plot planned a kidnap of James on his way south to the coronation. In the Main Plot, Brooke and Raleigh were supposed to have been negotiating for £160,000 of Spanish gold to fund installing Arbella on the throne.

With the plots’ Puritans and Catholics trusting neither each other nor their co-religionists, both were almost certainly doomed from the start. Arbella wasn’t boyled to death in hot scalding water, but, despite her reluctance, was imprisoned in the Tower of London, as were Brooke and Raleigh. Friendship only took you so far in Elizabethan England and it was Brooke who had implicated Raleigh.

Arbella died in the Tower in 1615. From prison, Raleigh attempted his own herring-based bid for favour in Observations Touching Trade and Commerce, which he wrotefor James in 1605. It makes the economic case for the adoption of a Dutch-style herring buss fishery (a Stuart aim since the reign of Scotland’s James III and a key element in the later downfall of Charles I). It didn’t work and Raleigh was eventually executed in 1618. Brooke was released the same year, a broken man. His wife, Lady Frances, had had absolutely nothing to do with him since the trial. He died shortly after his release.

Robert Cecil, who oversaw the Main and Bye Plot trials, played a notoriously long game with conspiracies. If Nashe had picked something up, he’d have had his red herring irresistibly banged to rights. The story might have provided the more resounding bel-metall in his pen, he telegraphs so early on in Lenten Stuffe, whilst at the same time being a little premature for Cecil.

Coming out of his fourth fancy, he most particularly defies anyone to find a meaning in it: O, for a Legion of mice-eyed decipherers and calculators uppon characters, now to augurate what I mean by this: the divell, if it stood upon his salvation, cannot do it.

THE ENDING

Henry V was first performed in 1599, probably after Nashes Lenten Stuffe was published. Nicholl suggests Nashe was finalising his text in mid February. His ending is glorious. He takes things back to Oldcastle and the Brookes (if you don’t like the red herring comparison, he suggests, I can easily come up with worse). There’s a suggestion of Falstaff (My conceit is cast into a sweating sicknesse). But the final lines, if anything, suggest just a little mockery of Henry V’s Cry ‘God for Harry, England, and St George!’ Back in London in late 1598, Nashe could have picked up a fragment of the play in development – from Shakespeare or from the actors.

Alas, poore hungerstarved Muse, wee shall have some spawne of a goose-quill or over worne pander quirking and girding, was it so hard driven that it had nothing to feede upon but a redde herring? another drudge of the pudding house (all whose lawfull meanes to live by throughout the whole yeare will scarce purchase him a red herring) sayes I might as well have writte of a dogges turde (in his teeth surreverence). But let none of these scumme of the suburbs be too vinegar tarte with mee; for if they bee, Ile take mine oath uppon a redde herring and eate it, to proove that their fathers, their grandfather, and their great grandfathers, or any other of their kinne were scullions dishwash, & durty draffe and swill, set against a redde herring. The puissant red herring, the golden Hesperides red herring, the Meonian red herring, the red herring of red Herrings Hal, every pregnant peculiar of whose resplendent laude and honour to delineate and adumbrate to the ample life were a woorke that would drinke drie foure-score and eighteene Castalian fountaines of eloquence, consume another Athens of facunditie, and abate the haughtiest poetical fury twixt this and the burning Zone and the tropike of Cancer. My conceit is cast into a sweating sickness, with ascending these few steps of his renowne; into what a hote broyling saint Laurence fever would it relapse then, should I spend the whole bagge of my winde in climbing up to the lofty mountaine creast of his trophees? But no more winde will I spend on it but this: Saint Dennis for Fraunce, Saint James for Spaine, Saint Patrike for Ireland, Saint George for England, and the red Herring for Yarmouth.

WHAT’S IT ALL ABOUT?

There have been a lot of could suggests and might means in all of this, but that is Nashe’s deliberate aim. Shakespeare ultimately found Falstaff a greater creation than Oldcastle or Fastolf deserved. Likewise, Nashe found his red herring to be far richer in possibilities than its nominal target, the nibbling cob, Henry Brooke.

Some, including CS Lewis, suggest Nashes Lenten Stuffe is gloriously about nothing at all. Kristen Abbott Bennett identifies a modeling on Erasmus’ The Praise of Folly and his colloquy Concerning the Eating of Fish and, as mentioned, sees it freighted with subversive indictments of arbitrary privilege. Erasmus couldn’t stand fish and had a dispensation from the Pope allowing meat eating at all times, which adds another beautiful layer of comic subversion.

Charles Nicholl sees it as:

A hymn to the inexhaustibility of language, a quirky pageant of responses and reverberations. The red herring is, in the axiomatic sense, a complete red herring, and as such it is Nashe’s metaphor for life itself. His ‘prayse of the red herring’ becomes a paradigm for the mind’s peripheral agitations around an elusive, perhaps non-existent, core of meaning. And if the red herring tells us life’s secret, then that secret is the plain fact of survival. The metaphor doubles back: the herring is food on his plate, the ‘stuffe’ of life in a hard ‘lenten’ world.

I’m happy to buy all of the above, although I’d err towards Nicholls – if only for the sense of Nashe that emerges. In a plausible analysis, Bennett seems to miss what feels like the genuine affection for Yarmouth’s fishermen, not to mention the endearingly manic, irrepressible and spontaneous joy Nashe takes in words.

There’s much more to read into it than I’ve included in this sketch, but for my own twopenn’orth, I’d also note Nashe’s red herring is both strong meate and, obviously, not-meat. It comes down from Heaven as Jupiter-made-flesh. Hero the herring is flesh-made-fish. As King of Fishes, each herring in the shoal is a King of Kings – and it’s interesting that Nashe has his Pope claim to be this, too. The Pope’s kitchen provides a scene not unlike the Harrowing of Hell. The red herring rises again to Heaven in the smoke, the fumes and its own canonisation. For Puritans, Oldcastle was martyred by a Catholic ecclesiastical court, but while Brooke remains the butt of the joke, Nashe’s mockery carries more than a hint A plague o’ both your houses! Even, all your houses. He has moved on from the pious farewells to fantastical satirism, he proclaimed in Christ’s Teares Over Jerusalem. There’s more than a whiff of the atheism of which Marlowe was accused.

Everything is deniable and nothing is said, but in the limitless word world he is conjuring it isn’t just royal and/or guild privilege he’s (not) talking about. All organised religion, the Christian mystery and even the principle of religious faith seem to be breathtakingly (not) fair game for his pen. All of it is there and not there, intriguingly just a little bit beyond our grasp. While, at its heart, it’s just the cheap, ubiquitous red herring of the poor and all Nashe claims from posterity is recognition that, I am the first that ever sette quill to paper in prayse of any fish or fisherman.

He had made his return to London with Lenten Stuffe: a penniless, gag-toothed, prodigal son, grinning: Come on! You’ve missed me! He’d been living on charity and unpaid debts for months, beyond the pale of patronage, unable to earn even the precarious living of a writer. Lenten Stuffe is the confounding of all his enemies. It is a cry of defiance at a world of privilege, which finds value neither in his life nor his work. He has his wit, however, and his words and, out of nothing, he can spin a world and a shoal of meanings of which he will allow himself only to be master.

CODA

Lenten Stuffe was published by Cuthbert Burby during Lent 1599. On 1st June 1599, together with a number of specifically named satirical and/or unseemly works, John Whitgift, Archbishop of Canterbury, decreed from his palace in Croydon, that all Nashes bookes and Doctor Harveyes bookes be taken wherever they maye be founde, and that none of theire bookes bee ever printed hereafter.

Books were burnt. In the tension and paranoia of the late Elizabethan age, sensitivities had been tested and had snapped. Seven years earlier Nashe had stayed at Croydon Palace, the guest of Whitgift. He’d written Summers Last Will and Testament there. Everyone had been sheltering together from the plague. Members of the Archbishop’s household had been involved in the performance.

Burby published Summers Last Will and Testament in late 1600, maybe testing the waters: it’s a play rather than a satirical poem or pamphlet and it had a connection to Whitgift’s own patronage. Nashe seems to have had a hand in translating Tommaso Garzoni’s The Hospitall of Incurable Fooles, published that same year, but when you’re being officially erased from history it can be lean pickings.

He died in 1601. In the many links to texts, included at the bottom of this entry, there is one to Ben Jonson’s Elegy on Thomas Nashe. The poet Charles Fitzgeoffrey also wrote a Latin epitaph, which has been interpreted as suggesting either that he died of a stroke or as a result of poverty inflicted by authority. In the spirit of Nashes Lenten Stuffe, a combination of two is not impossible.

Either way, a big heart gave out.

THOMAS NASHE

When Death, upon imperial Jove’s command, obeyed,

Extinguishing the vital spark of Nashe with night,

First, with stealth, he seized those twin thunderbolts,

That young man’s battling tongue, his fearsome pen,

So he could move upon one naked and unarmed,

Bringing back in triumph the poet as his trophy.

Had pen or tongue been left available to Nashe,

He would have struck the fear of death in Death himself.Charles Fitzgeoffrey (trans: Herripedia)

Acknowledgements, etc

I first read Nashes Lenten Stuffe at Cambridge in 1972. The great Brian Vickers was taking us for C16th & C17th literature, not long before he headed off to become professor at ETH Zurich. Possibly in despair at my responses to Sir Philip Sidney or Edmund Spenser, he encouraged me towards Thomas Nashe and Robert Greene. I happily worked my way through most of the texts in McKerrow’s Works of Thomas Nashe. I came nowhere near a full understanding of Lenten Stuffe at the time (and I wouldn’t claim that yet) but I fell in love with its spirit, even though I knew nothing about herrings. I doubt if what I wrote had much, if any value, but it stayed with me – for which much thanks.

In 1998, when I was commissioned by Sue Roberts to do the BBC Radio 4 series Rigby’s Red Herrings, I went back to Lenten Stuffe. In the twenty or so years I’ve worked on the herripedia, I’ve read it a few times. Each time it has been more rewarding.

Charles Nicholls’ A Cup of News: The Life of Thomas Nashe (Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1984) is great and I’ve drawn on it extensively. I don’t think we ever met, but he was at Cambridge while I was there. Clearly, he worked far harder than I ever did.

When you’re chasing down texts and references these days, the internet is fantastic. While I was looking for something related to this entry I came across Kristen Abbott Bennett’s Red Herrings and the ‘Stench of Fish’ (Renaissance and Reformation, Vol 37, No 1, 2014, pp 87 – 24), which was both interesting and helpful. There’s not a huge amount of work on Nashe. I read one or two others that didn’t give me much. There were one or two other pieces I’d have liked to have read, but they’re harder to access without being at a university or paying on spec.

I’m particularly grateful to HS Fish of Great Yarmouth for having let me visit when I was working on the radio series. The buisness closed in 2018. I interviewed the last two red herring producers back in 2021, both in Lowestoft. Will Buckenham’s business, which was in the country’s oldest working smokehouse, was a victim of COVID, so if you would like to eat some red herring (and I’d urge you to do so) get it from Gerry Skews at Waveney Valley Smokehouse – you can order it online.

External Links

- Nashes Lenten Stuffe, text, original spellings

- Nashes Lenten Stuffe, text, modern spellings (misses some word play)

- Henry IV, Pt 1, text

- Henry IV, Pt 2, text

- Henry V, text

- Merry Wives of Windsor, text

- Every Man in his Humour, text

- Ben Jonson's Epigram XL: On Margaret Ratcliffe

- Ben Jonson's Elegy on Thomas Nashe

- Mercury Vindicated from the Alchemists, text

- The Masque of Augurs, text

See also

- AQUINAS, ST THOMAS

- BATTLE OF THE HERRINGS (1429)

- BLOATER

- BRITISH FISHERY

- BUSS

- DIVINE PROVIDENCE

- DUTCH GRAND FISHERY

- ENGLAND’S PATH TO WEALTH AND HONOUR

- ETYMOLOGY

- EUPHEMISMS

- EYVIND SKÁLDASPILLIR

- FASTING

- GOLDEN HERRING

- HARENG SAUR

- HARENG SAUR MONOLOGUES

- HERRING BUSS (TUNE)

- KIPPER

- LOCKMAN, JOHN

- LOCKMAN’S VAST IMPORTANCE

- MARTYRED SAINT

- MIGRATION & MOVEMENT

- NASHES LENTEN STUFFE

- NEUCRANTZ: ON HERRING (1654)

- OLIVIER, LAURENCE

- PARA HANDY

- PICKELHERING

- PROCESSION OF THE HERRINGS

- PROPHETIC HERRINGS

- RED HERRING

- RING NET: WILL MACLEAN

- SALT

- SHOALS

- SHOALS OF HERRING, THE

- SMOKEHOUSE TALES: GERRY SKEWS

- SMOKEHOUSE TALES: WILL BUCKENHAM

- SOVEREIGN OF THE SEAS

- SWIFT, JONATHAN

- WHEN HERRINGS LIVED ON DRY LAND

- WHITE HERRING

- WILLIAMS, WILLIAM CARLOS: FISH

- WITCHCRAFT