An historical journey through the extraordinary world of Norwegian sardine can labels, known and collected in Norway as iddiketts or iddis

IDDIKETTS OR IDDIS

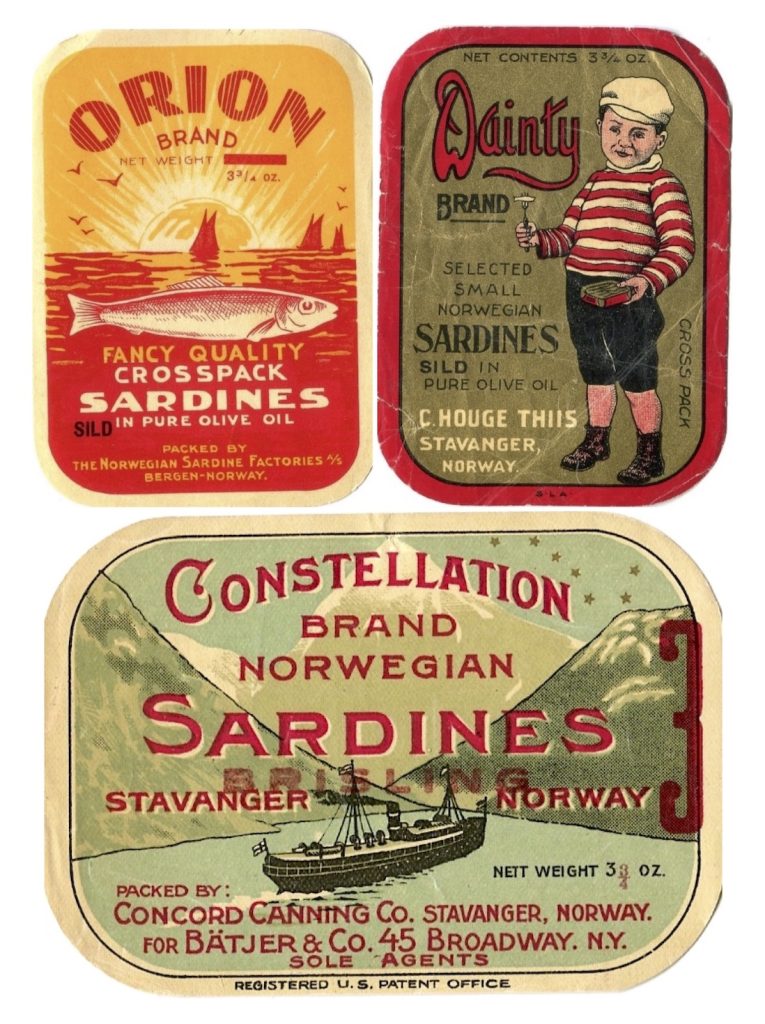

Canning food developed out of bottling. Use clear glass and the thing is, you can see what’s inside a jar. Tins need labels and the Norwegian for label is etikett. Maybe in Stavanger, at the beginning of C20th, there was a shortage of stamps and cigarette cards, but in a frenzy of street corner excitement this was the when and where of sardine can label collecting’s beginnings. Before it was Oil Capital of Norway, Stavanger was its Sardine Capital. Etiketts became iddiketts (it’s the way they talk in Stavanger) and iddiketts became iddis (singular and plural). Stavanger, at the time, was a city of only 30,000 people, small for a capital of anything, but this may have contributed to the idiosyncrasy of iddis culture.

The Images

The curious stories of the sardine can are more than matched by the curiosities among its labels. This entry has its narrative byways, but the images will more than make up for any of its failings.

Unless otherwise stated, they have been drawn from the collections of Iddis, Museum Stavanger’s print and sardine can museum (MUST/Norwegian canning museum) and the iddis collectors organisation, Iddisklubben Norway Brand. Links to their online presentations are included at the end. Days can be spent exploring the MUST and Norway Brand presentations. Trust me.

PART ONE: A LITTLE BIT OF HISTORY

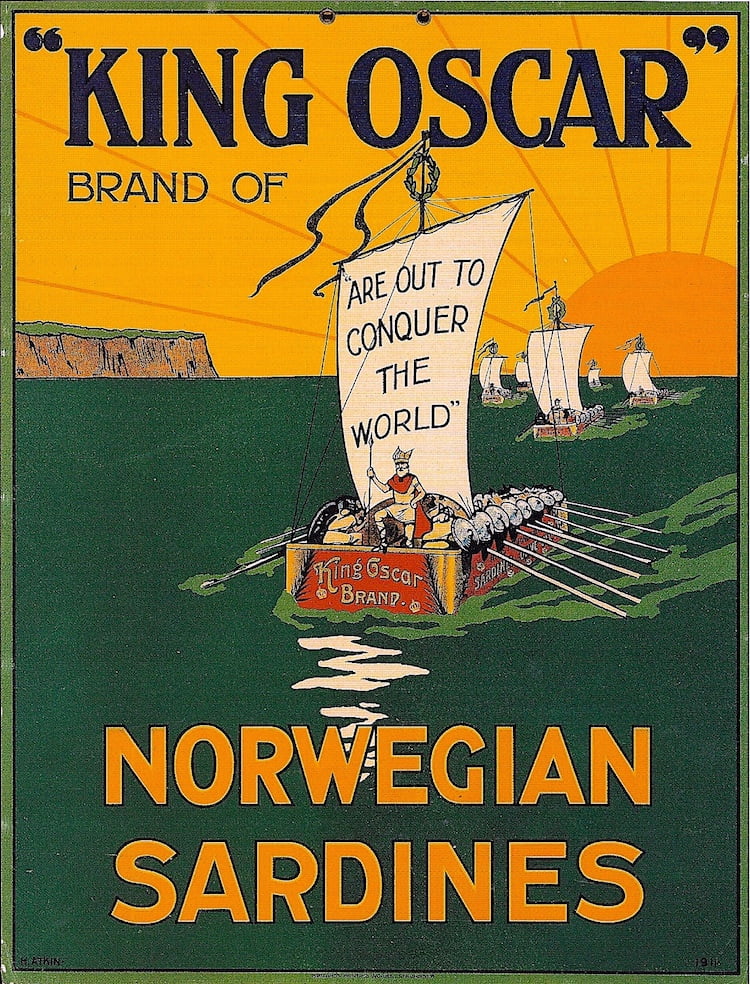

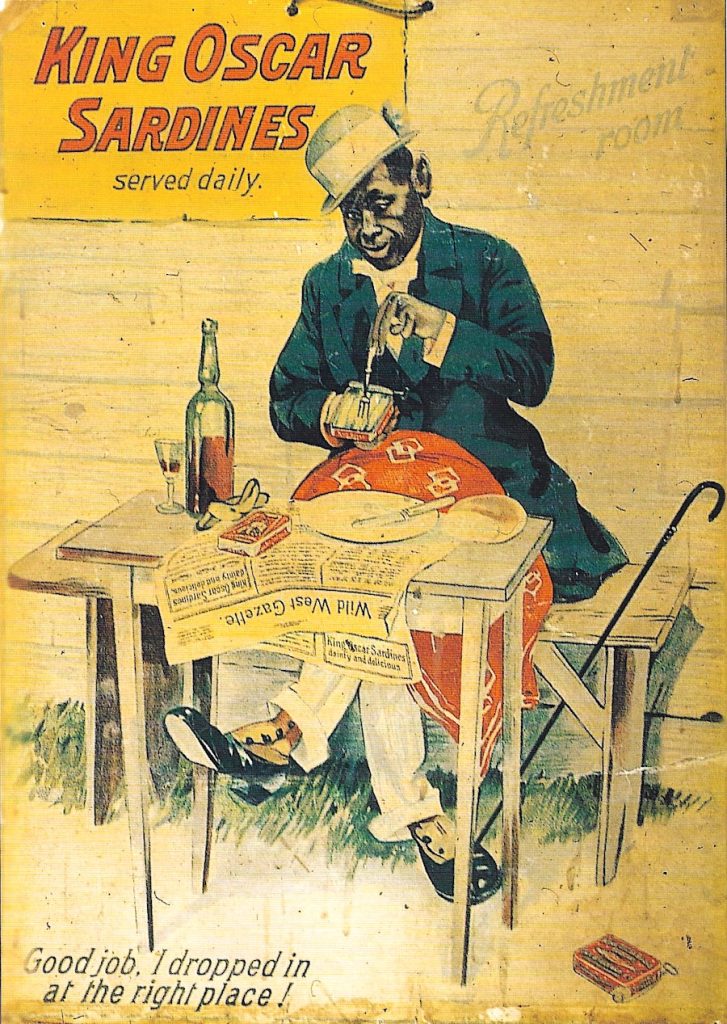

Identifying Norwegian canned food contents began with printed strips of paper, but it developed around the the strength of the sardine trade’s commercial context and the tin’s iconic standard format. An early shop display poster for Christian Bjelland & Co’s King Oscar brand, celebrates their export ambition as a canned revival of Viking trade across and beyond the known world. It relies on Norway’s C20th international image being almost entirely positive. The raiding that once accompanied the trading was far enough in the past to be just a salting of the joke. But the ambition was formidable, founded in technology-driven opportunity and juvenile shoals widely regarded as a limitless resource.

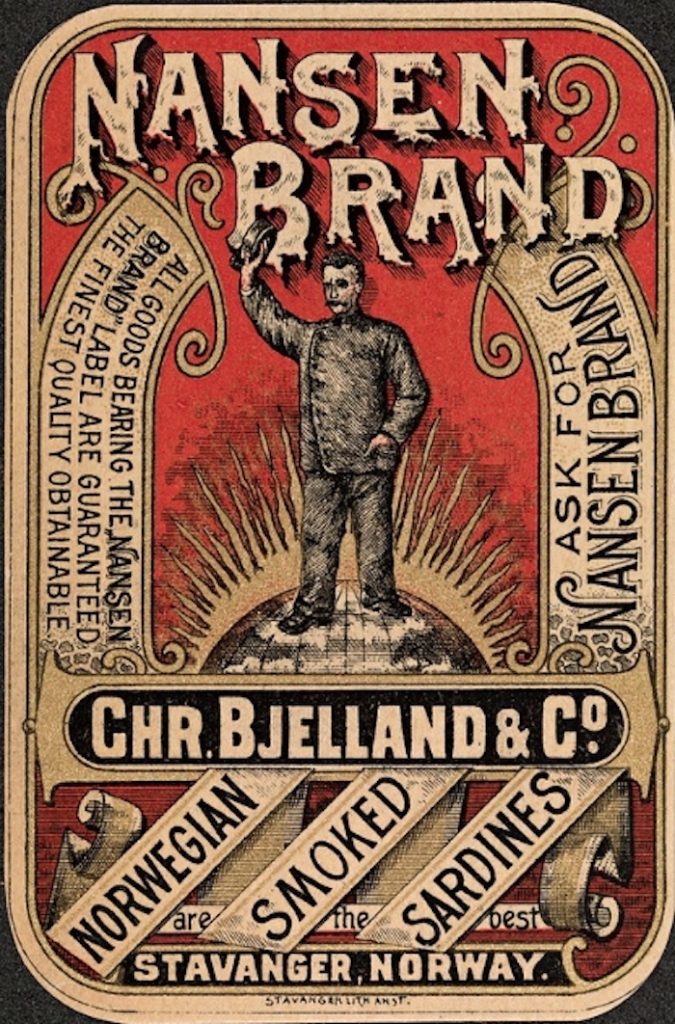

The overwhelming majority of iddis were created for the 1/4 Dingly: the classic sardine tin with a lid measuring 75mm x 105mm. In their heyday, the bulk of designs were vertically formatted. Bjelland’s were responsible for what is seen as one of the earliest, a Nansen Brand from 1896. Fridtjof Nansen had crossed the icy wastes of Greenland in 1888. His Fram expedition of 1893 to 1896 had reached 86°13′6″N, which was closer to the North Pole than anyone else had achieved.

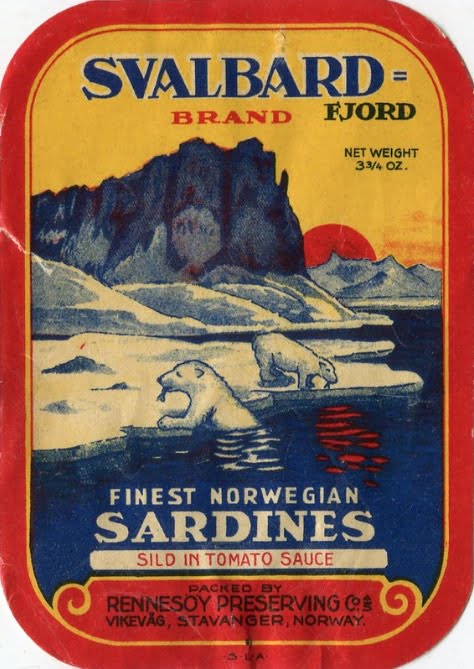

Later Norwegian North and South Polar explorer Roald Amundsen was also iddis-ed, along with his airship Norge -and his friends the polar bears with their fondness for sprats and herrings, unremarked upon in standard reference works, but well-documented in Iddisworld.

With growing numbers of Norwegian canneries taking advantage of the growing sardine market, intense competition drove an extraordinary proliferation of brands and designs. Collecting iddis started as a children’s hobby, probably in the late 1890s. It was certainly in full flow by the early years of the C20th, although the mention in print had to wait until 1910, in the pages of Stavanger Aftenblad, where the president of the Norwegian Stamp Collectors Club, Bertrand Middlethon announced the intention to collect a full set. Whether this ambition was ever achieved is not known, but a number of albums were produced, each methodically organised by image type.

The labels lacquered paper had a stiffness and, as well as collecting and swapping them, the youth of Stavanger made (small) model boats and aeroplanes with them. They also became a kind of scrip for gambling on games of marbles. It must have been the big players on the scene who developed sjeining or throwing large numbers into the wind, presumably to watch children less fortunate scramble for the treasure.

How could anyone eat enough sardines for such largesse? Stavanger was a small city, but obviously a wild town. In the same year Middlethon had legitimised these new collectibles, Stavanger Aftenblad broke the story of a printers’ boy robbed on the street of an 8,000 label delivery. With or without polar bears, it was the tip of an iceberg: The regular thefts label printers report result from this collecting craze. Parents must be aware of the temptations this craze is spawning. It is clear such quantities of labels can only be obtained by devious means. Unaware that they were corrupting their own children, some printworkers probably fuelled the craze with discards and excess production.

Stavanger combined the Canning Museum with its Print Museum to create Iddis, which opened in 2021. Housing a collection of around 11,500 different labels, it has so far published 2,400 on DigitaltMuseum. At time of writing, Norway Brand presents 117 pages of labels on Flickr at 100 to the page. Records suggest 30,000 or more different designs may have been created.

The first pressure steam steriliser or autoclave came along in 1876. It transformed shelf life. The cans themselves, however, still relied on hand-soldered seals. Machine-folded sealing for the rectangular sardine tin was developed at Stavanger between 1900 and 1912, when Nessler’s Machine Workshop launched its fully automatic seamer. Progress cost a lot of solderers their jobs, but at the same time it reduced prices. The French eventually had their own machines, but they were slower off the mark and their sardine prices were undercut.

From cigarettes to soap, the British had had considerable success slapping Queen Victoria pictures on products. Bjelland, who’d started producing hermetically sealed sardine tins in 1893, noted this. He registered the King Oscar Brand in 1902 and it quickly came to dominate the export market. On Oscar labels, you sometimes find the king framed in his own conceptual key-opened tin.

The key dates from 1866. The Norwegians first deployed it on their sardine cans in the 1890s and it became a selling point. The key-opened sardine can became an icon, helped by the iddis designers who clearly loved it. Beyond mere convenience, it sang of the modern age.

On the Oscar tins, intentionally or not, there’s more than a hint of the guillotine about the can-within-the-can. Things never went that far, but in truth Oscar II of Sweden and Norway (1829 – 1907) wasn’t that popular in Norway, which wanted independence and achieved it three years after Oscar was crowned as a sardine brand. Whatever his failings as a king of men, as King of Sardines he bestrode the world and if export markets didn’t worry about the details of Scandinavian monarchy, why would the Norwegians?

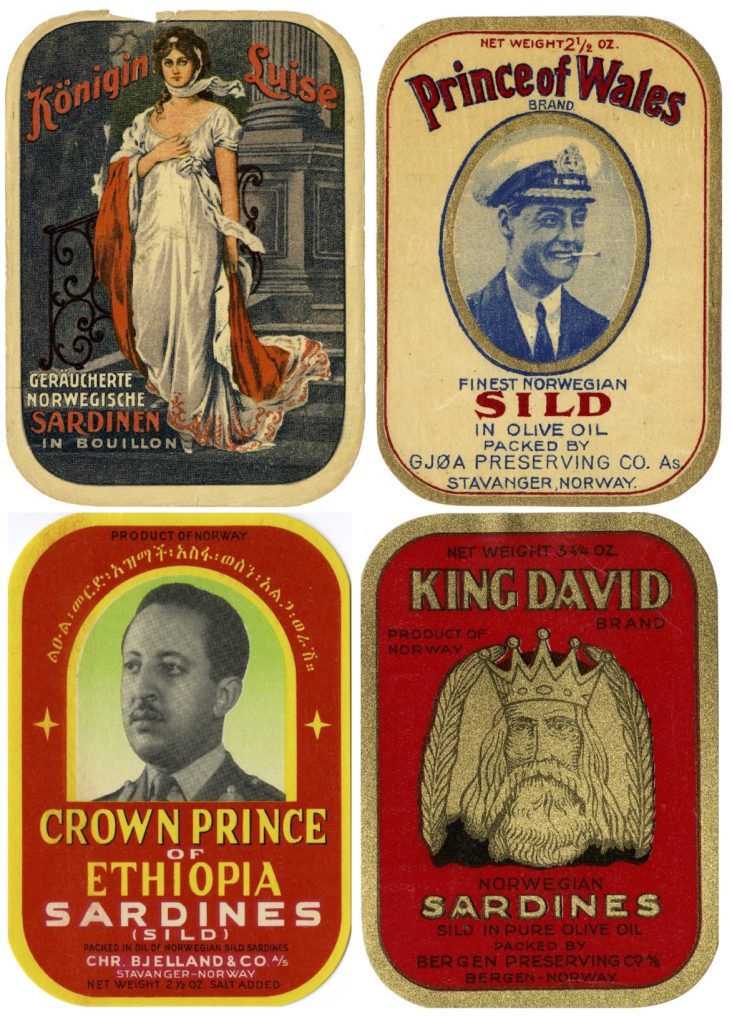

With royal branding seen as integral to Bjelland’s success, other canneries followed suit. Norway had invited Denmark’s Prince Carl to come and king for them as Haakon VII, but Einar Hausvik’s of Bergen beat Bjelland to the brand. Hausvik’s were successfully sued for plagiarising Bjelland’s red and gold King Oscar design, but the genie was out of the bottle and any royal with perceived market resonance would do.

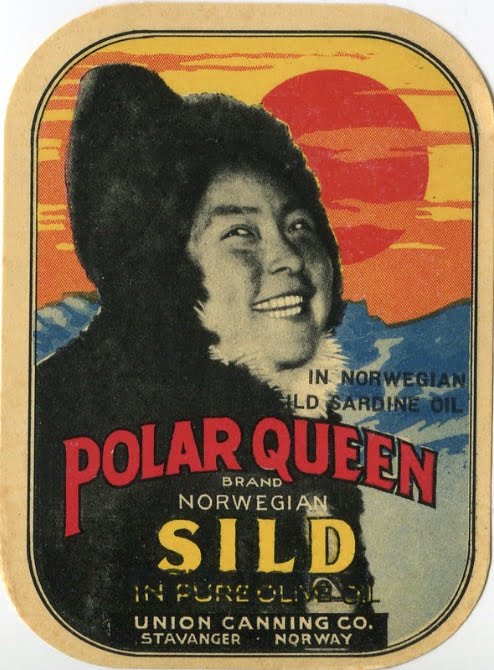

Other sardine can royals included: King Olav, King Magnus, King Halfdan, King Ragnar, King Knut & Canute, King Cedric, King George, King Charles, King Richard, King Roland, King Umberto, King Saul, Queen Estelle, Queen Mary (as an ocean liner), Queen Maud, Regina, Sovereign Queen, Sea Queen, Polar Queen, Norse Queen, Northland Queen, Snow Queen, Coral Queen, May Queen, Beauty Queen, Prince Olav, Prince Paul, Crown Prince, Prince Viking, Prinse Sild, Princess Astrid, Princess Martha, Prinsesse Sursild, Old King, Fish King, King of Brisling, King of Diamonds, King Neptune, King Lear, King Arthur, even old King Cole.

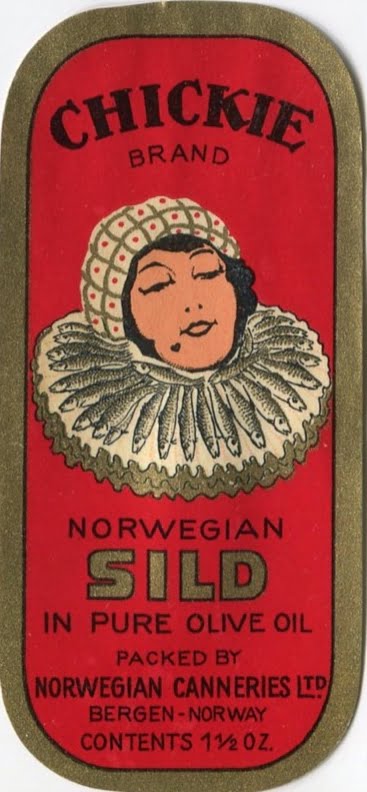

For those customers who just wanted to feel like a queen, the Chickie Brand invited them to ease their heads back and dream in the caress of that lost fashion accessory, the sardine ruff.

The Great Sardine Litigation

So, why is Chickie talking about sild again? At this point it’s worth introducing Newcastle upon Tyne grocery entrepreneur Angus Watson. Bjelland’s regularly sent out samples and Watson immediately saw their potential. He built his own fortune, marketing Norwegian sardines under the Skipper brand.

He’d worked for fellow grocery pioneer William Lever (Sunlight Soap, Lever Bros, 1st Viscount Leverhulme, Unilever) and had become a close friend. Like his mentor, Watson focused on quality control and healthy advertising budgets. A partnership with Bjelland’s was initiated in 1905 and he played a part in shaping the competitive arena of Norwegian Sardine production.

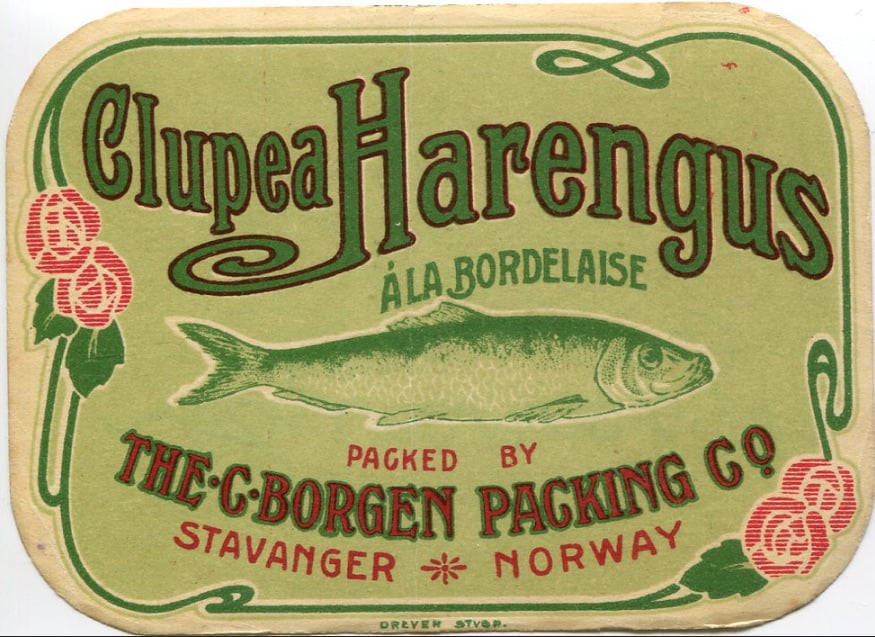

As members of the same family, pilchards, sprats and herrings have similar tastes and textures. French and Portuguese juvenile pilchards can be smoked but most are simply cooked in olive oil with a little salt. They’re also caught at a later development stage, when you can only fit four to a tin. Standard Norwegian sardines are taken closer to the whitebait end of things.

As their pilchard shoals recovered, the French were probably less concerned with Norwegian sardine sizes than their prices. Between 1905 and 1914 the still-hand-soldering French pursued litigation across Europe, insisting sardines could only be pilchards. They were ultimately successful, but didn’t pursue their case elsewhere. Across the world today twenty fish species are sold as sardines.

Angus Watson had spent £30,000 defending the Norwegian Sardine in London, but through newspaper What is a Sardine? advertising he also played shrewdly on British jingoism to move the focus from the sardine to the Skipper.

What is a Sardine? You shall be Judge and Jury, says the smiling, pipe-smoking, bearded and sou’ westered Skippers label fisherman, holding a can up at the back of the courtroom. Another advert reminds us, The price of ‘Skippers’ new pack has been reduced to 9½d per tin, while our now godlike fisherman holds in one open palm a crowd of happy Brits going about their business, in the other the two or three litigious Frenchmen who were trying to take our Skippers away:

At a great decisive test by a large number of the public, over 99 people out of every 100 preferred “Skippers” to the large, and often coarse, old-fashioned Sardines.

The public actually purchased tins of each. They opened each tin – the handy little “Skippers” tin with a turn of the key, and the other with a clumsy cut-the-hand-and-mangle-the-fish “opener”…

The shift from the bearded fisherman ‘Skipper’ towards the small fish as Skippers was genius. The actual Skipper, William Duncan Anderson, was an ex-sailor whose fine beard had enabled him to earn a bit by modeling. Even before the litigation, Skippers had become so successful and his face so famous, he couldn’t get work anymore. Watson put him on the payroll until the day he died.

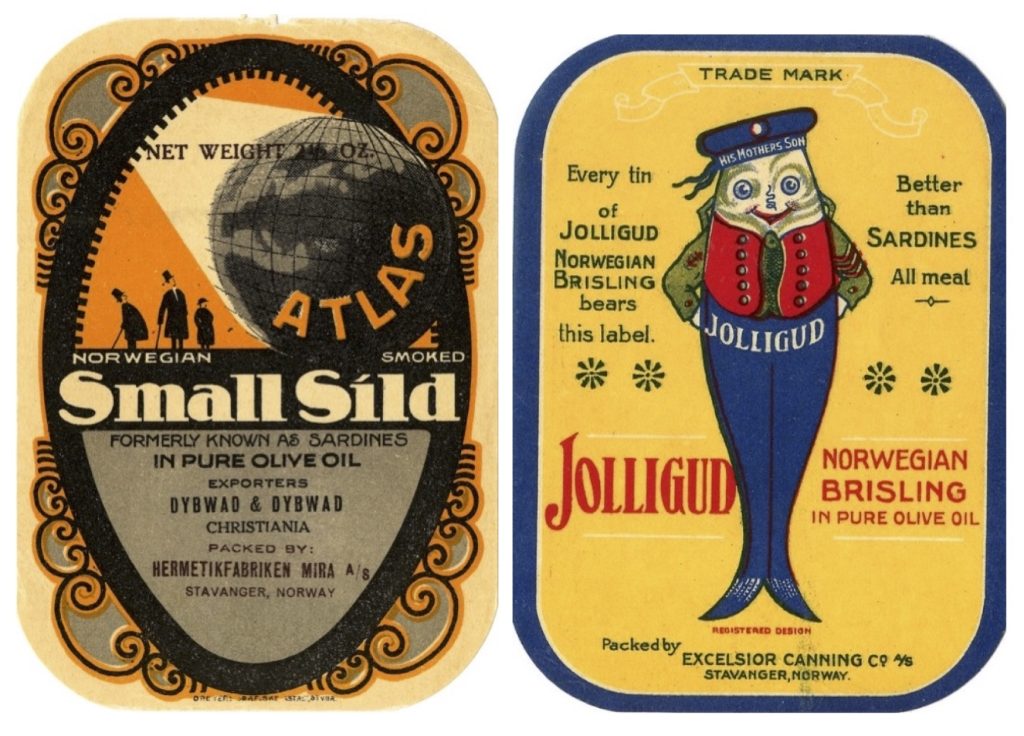

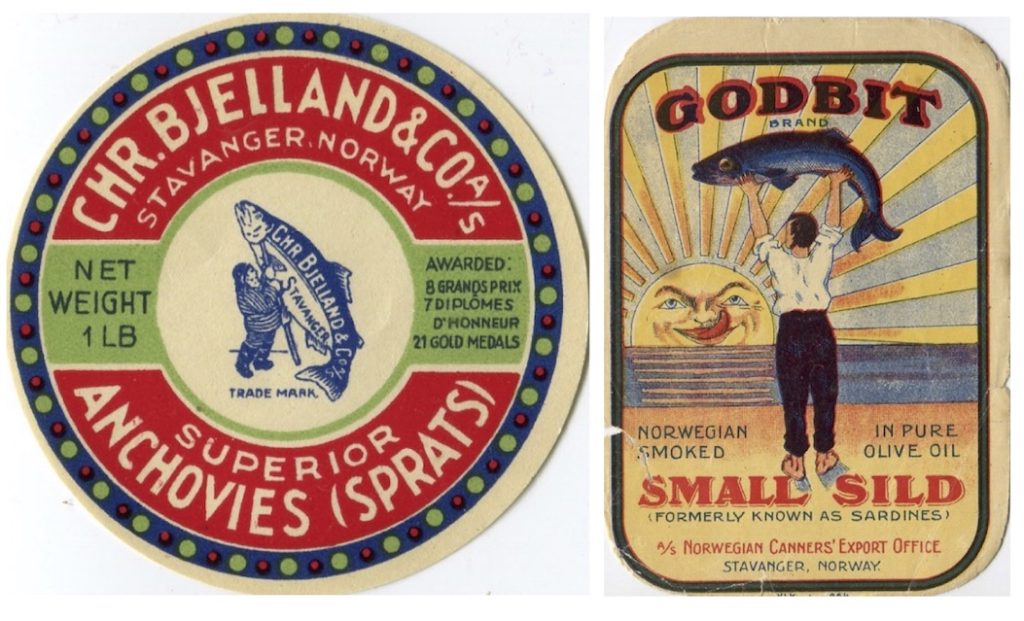

Watson’s own humorous and combative account of the litigation can be found at Sardines, but the labels had to change. You can track the adjustment across ones overprinted with SILD or BRISLING (sometimes even for the unaffected US market). You find Formerly Known as Sardines and Better than Sardines as well as attempts at emulating Watson with new names – Children love these tiny fish and have named them Scrumpies.

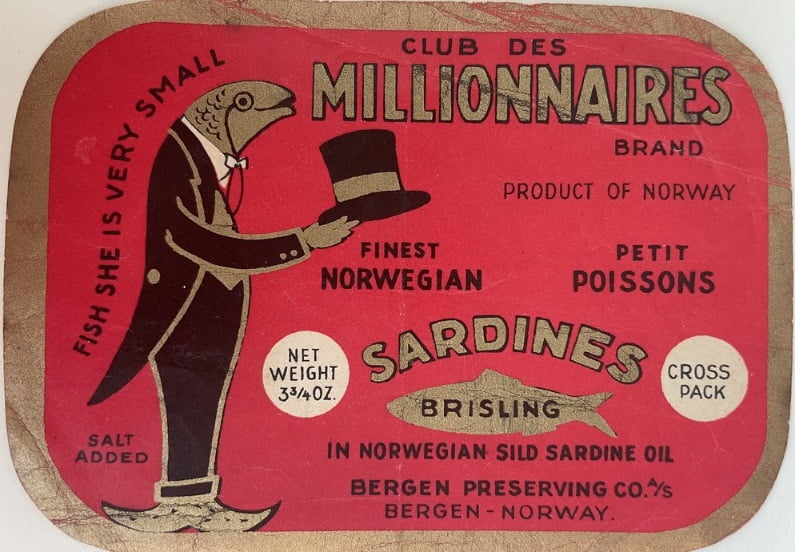

A number of iddis highlight fish size. It’s possible to argue, with more time to eat oil-rich plankton, the later-stage juvenile pilchards might have a richer flavour, but on the French Riviera, at the well-known Club des Millionaires, the waiters all assure us, Fish she is very small…

There are even labels which experimented with foregrounding the Linnaean taxonomic…

The brouhaha settled down, however, not least because, whatever you called them, Norway’s sardine exports continued to grow. By 1920 there were 120 sardine canneries in Norway. Sardine production had come to form 90% of the country’s canned food exports. Out of Stavanger alone, from 756 tonnes in 1895, sardine exports rose to 36,700 tonnes by 1915 – approximately 350,000,000 tins).

PART TWO: THE PICTURE ON THE TIN

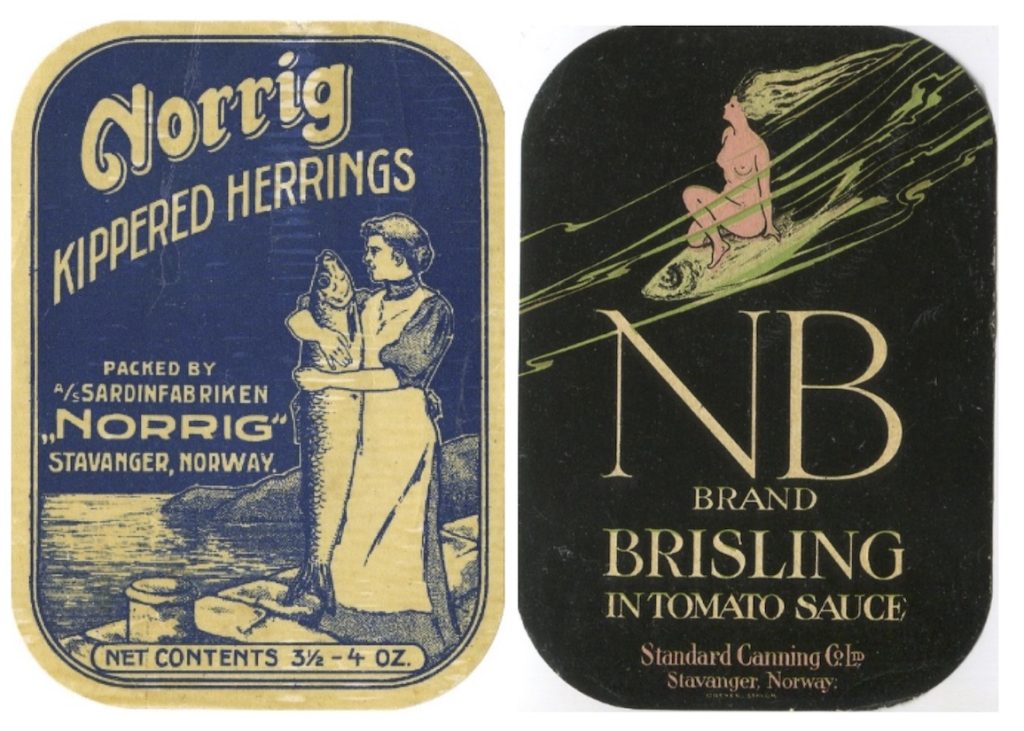

Beyond herring and sprat variations (unsmoked, Spring herring, fat herring, maatjes herring, kipper fillets, kipper bits, soft and hard roe, etc) Norway’s other tinned fish products: crabmeat, cod roe, eel in jelly, mackerel, mussels, peeled shrimps, salmon and more. There were other can formats, long, round, oval-shaped. All the labels are collectible, but 1/4 Dinglys are at the hobby’s heart.

Even with the huge success of King Oscar, Bjelland’s developed other brands. Skippers were Watson’s main focus, but he also had Tea Time for the sophisticated end of the market: set on a cruise ship, it comes with different couples, different tea services and mountains in the background, but the man is always frozen in the same offer of an opened tin.

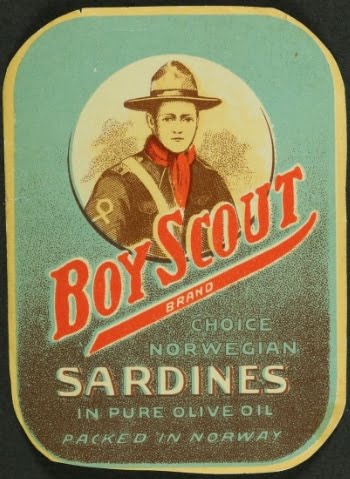

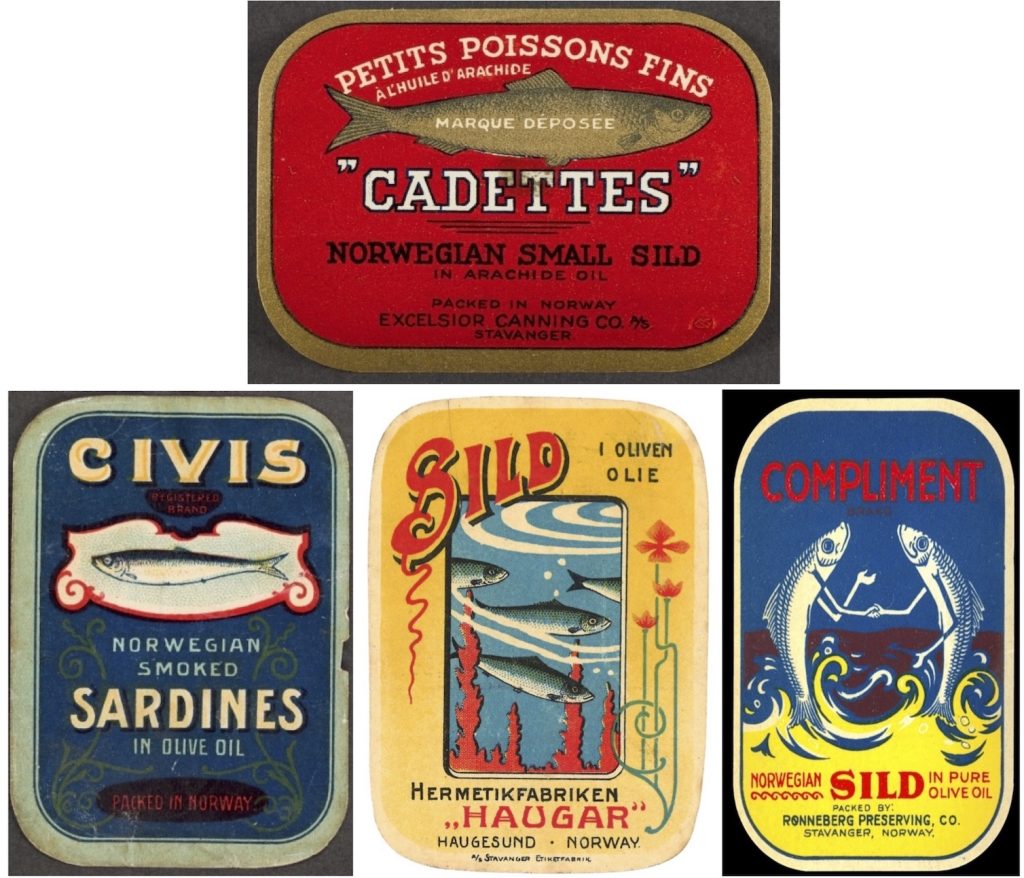

Tins were exported pre-labeled and, as brands and labels increased, Stavanger became a centre for Norwegian design and print. Iddis became even more accessible, by heist or persuasion, to young collectors. If they kept themselves clean in thought, word and deed, there might even have been a badge for it…

If the Norwegian Stamp Collectors Club had kept their albums going, methodical organisation would have been harder to maintain. We’ve had the royals, explorers and polar bears, but motifs proliferated and categories often overlap.

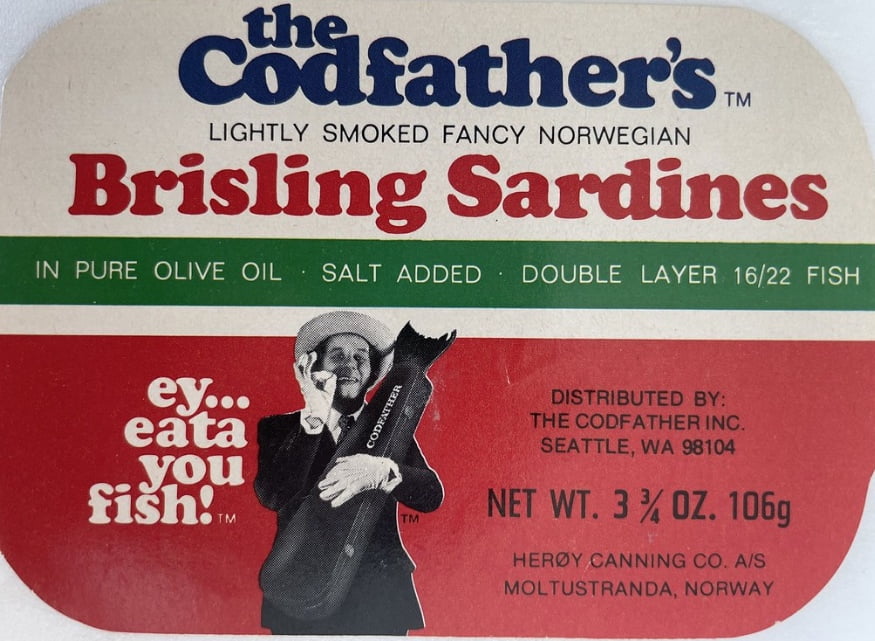

There are also labels so idiosyncratic they defy category. The 1970s Codfather’s with its album-cover Cooper Black, a white-gloved gangster, sporting what looks like a Norwegian farmer’s chinstrap and toting a salmon in his violin case isn’t a design classic (the heyday of the iddis was long gone) but it’s still off the wall.

The Fish and the Can

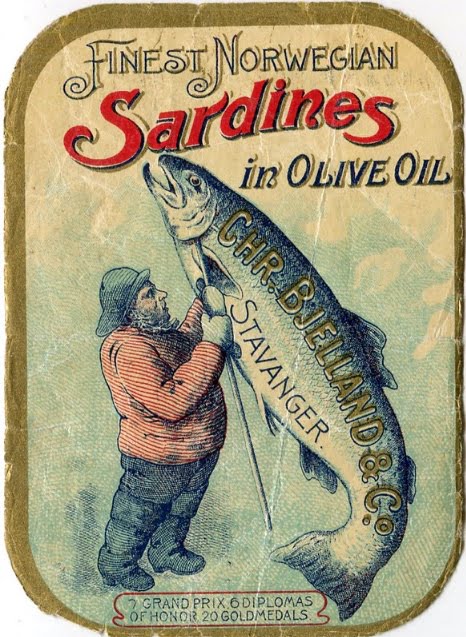

Bjelland’s got in early with their classic ‘Man with Big Fish’ design, created by the artist and folktale illustrator Theodor Kittelsen. The folktale quality it has is found on many iddis. Yes, as with the later Codfather’s, it’s a salmon, but let’s not get picky. Iddis often played fast and loose both with species and size. There’s a particular magic in the accentuated contradictions of scale.

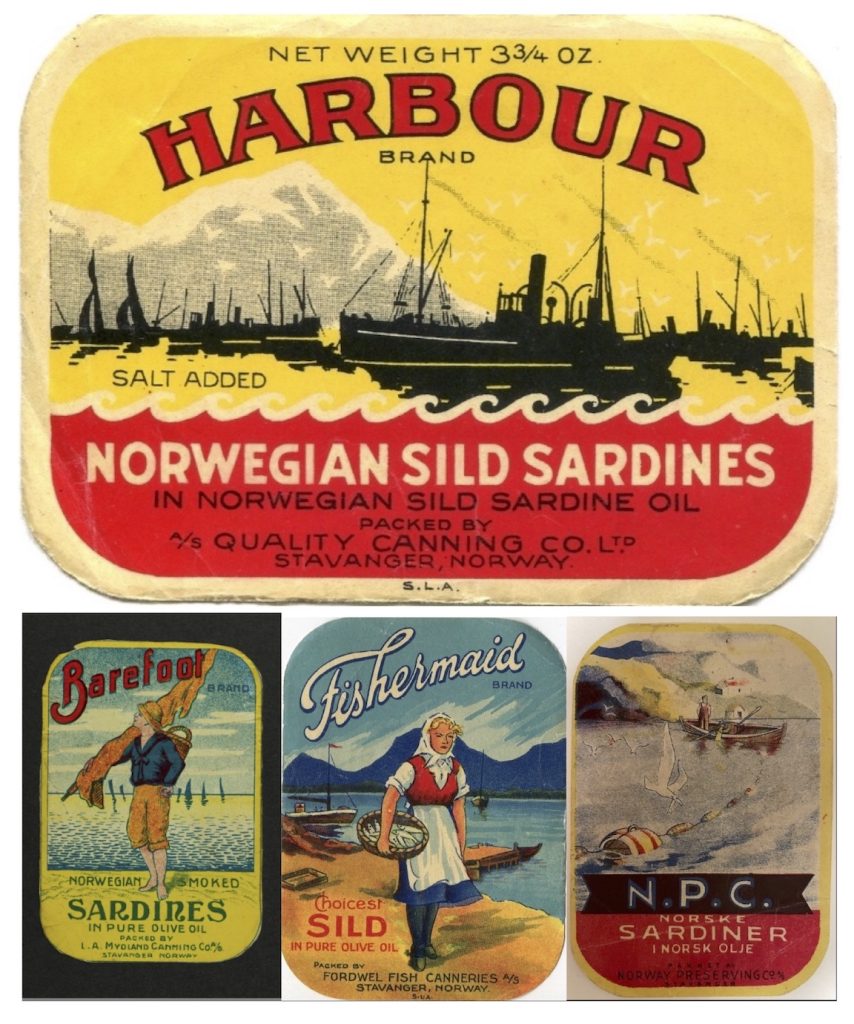

Sprats and herrings are, themselves, celebrated on a swathe of Norwegian sardine cans, singly, in shoals and, of course, shaking hands. And when they’re not containing kings, you often find the tins offered to you by beautiful young women, who seem to suggest something more is on offer than sardines on toast.

Like the fish, the cans can be scaled up. They can be Viking ships, of course, but they can be given wheels, forming wagon trains which drive themselves to market. Sometimes the sardines are so keen to be eaten they jump into those tins themselves; sometimes a little Water Babies style child labour might be involved.

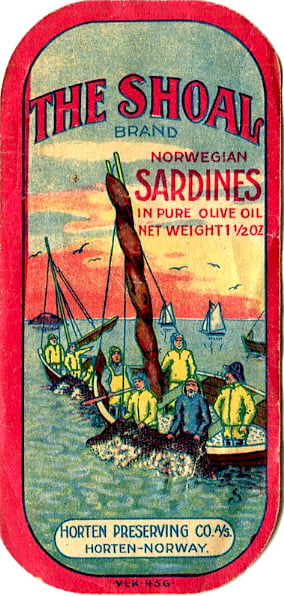

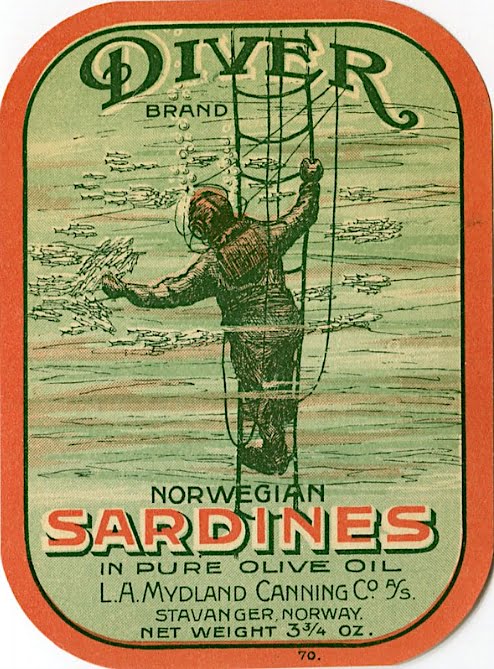

The Sardine Fisheries

Crowding the coastline, a fishing fleet testifies to the rich shoals: the bounty of Norwegian waters packed into every tin. Elsewhere, the labels celebrate fishermen’s simple virtues and the open-faced, welcoming beauty of the fisher lasses and factory girls. Open the can and dream of the good life!

Always at the industrial cutting edge, the cans can also capture Norway’s experimental approaches to sprat and herring fishery prior to World War I…

Norwegian Landscapes

The Bonnie Lassie Brand plays to British markets with its Scottish fisher lass. In the same way, landscapes from other parts of the world can be celebrated on the iddis – usually well-known beauty spots. For dramatic beauty, however, who is going to trump Norway. One can say, with confidence, its coastline beats the Bay of Biscay where those Frenchmen continue to fill their inconvenient cans…

So deep and so clear, the fjords of Norway hold so many shoaling teatime delights! The air itself naturally exudes health and happiness. Drink in that freshness and forget your smogs and sunless streets.

Norsemen and Norman Conquerors

When you’ve associated enough with Norway’s beautiful fjords, turn your thoughts towards its Norsemen and the kind of strength your children will need in their daily battles. As Bjelland’s poster reminded us, the Vikings’ trading networks once stretched from Kiev to the New World, from Iceland to Istanbul… Today they stretch even further! And Norsemen can be kings or Norman Kings of England, Scotland, Sicily and half of France. You can’t have too many kings.

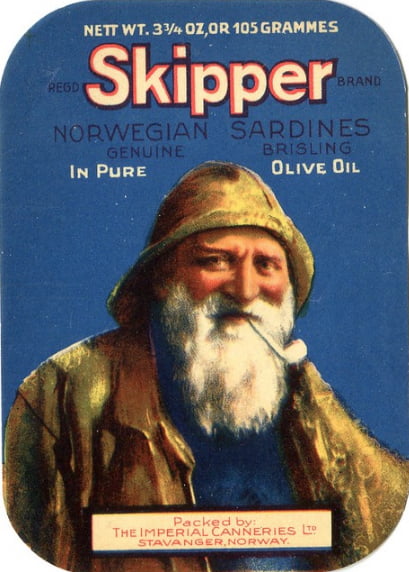

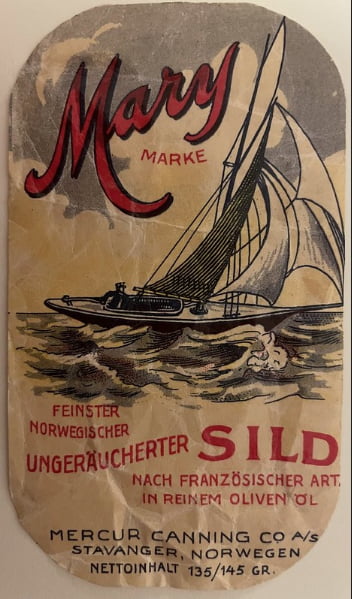

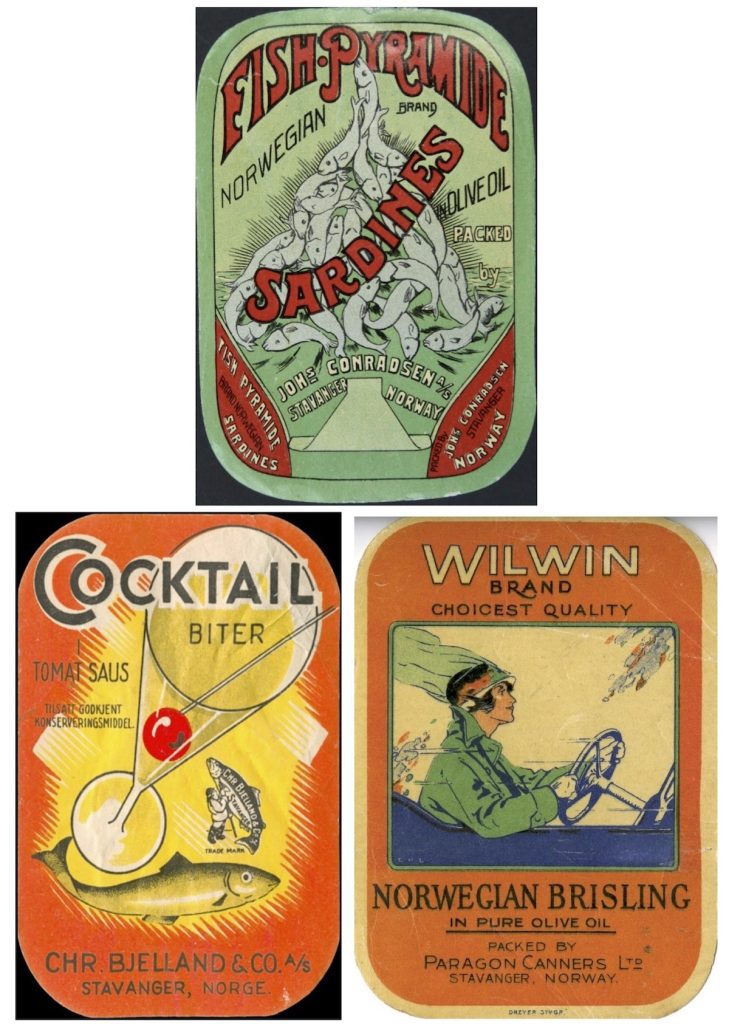

Transports of Delight

But this is the C20th! If anything can truly represent the Modern Age, surely it’s the transport revolution. Motor cars, ocean liners, steam trains, airships and biplanes were all regular iddis motifs. Aspirational for most of the sardine buying public, with their speed and range they bring a sense of hope in the future and what it will deliver, along with the tins sardines themselves, which, even now, are crossing oceans to be with us!

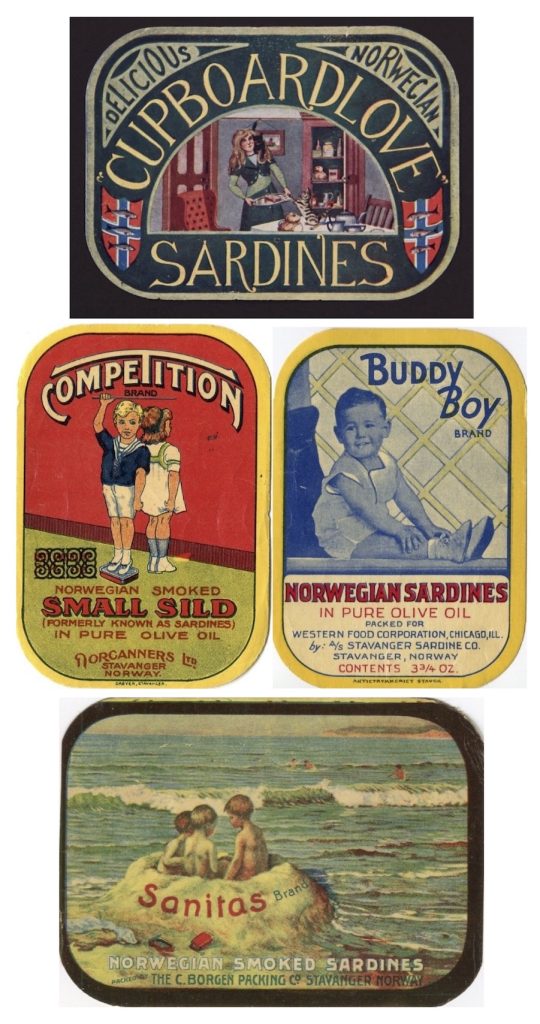

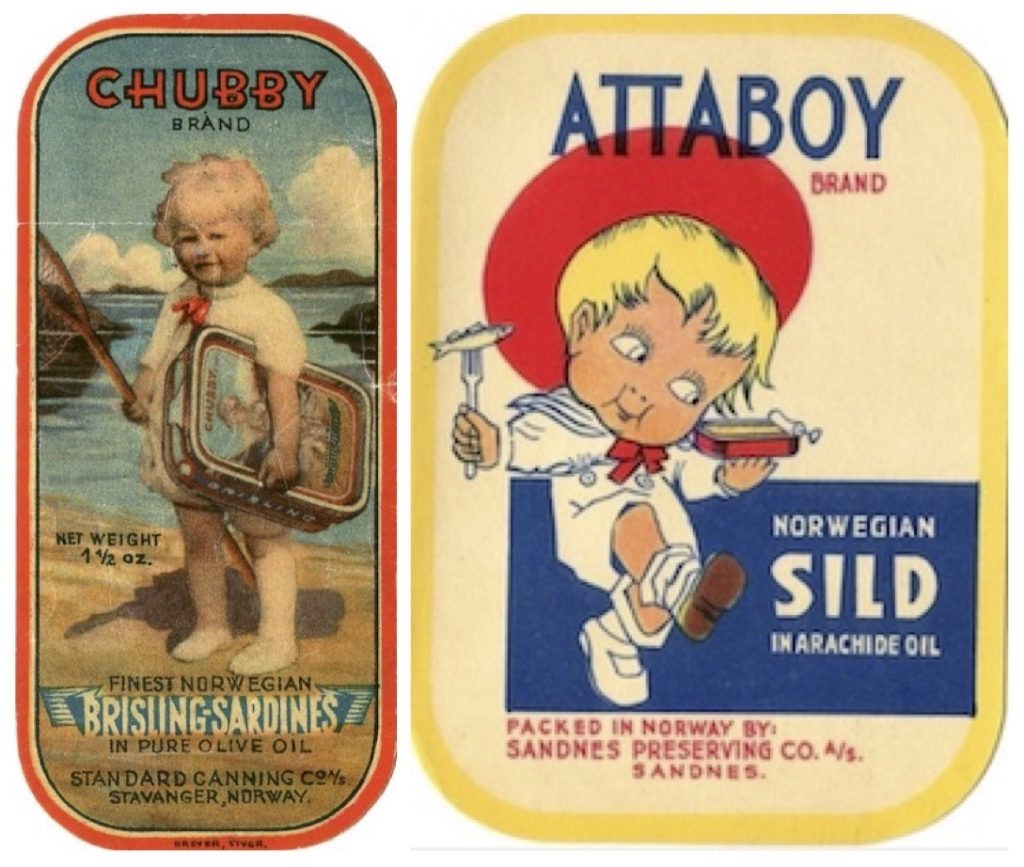

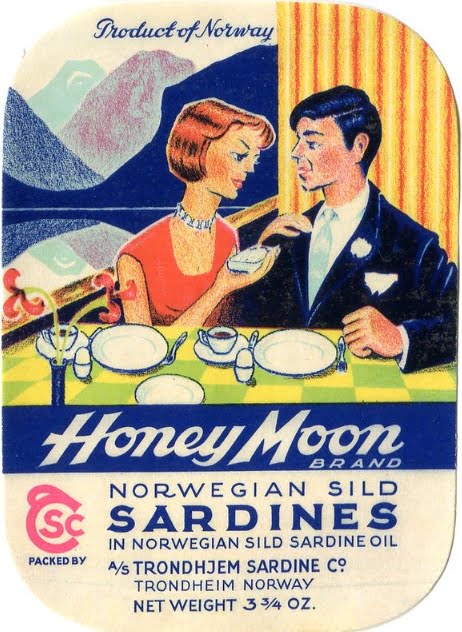

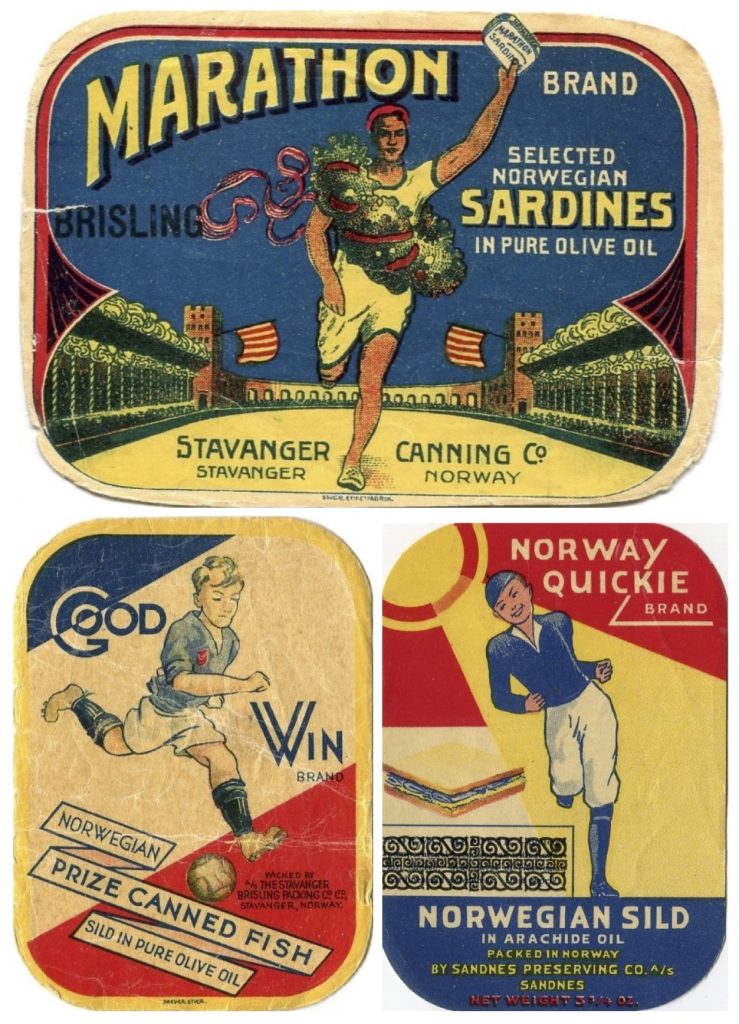

Healthy Happy Families

Sardines swim at the heart of every healthy, happy, growing family. Before anyone had ever heard of Omega 3, they were signifiers of a mother’s love and, more than that, downright responsible parenting. The nutritional value of sardines is pictured through the children, some of whom also provide brand names: Sonny, Junior, Lester, Bjarne, Joy, Sonja… Boys’ names outnumber girls’ names here, almost by as much as those of young iddis women come to outnumber men. Meanwhile, we shouldn’t forget the family dogs, Dandy and Patsy.

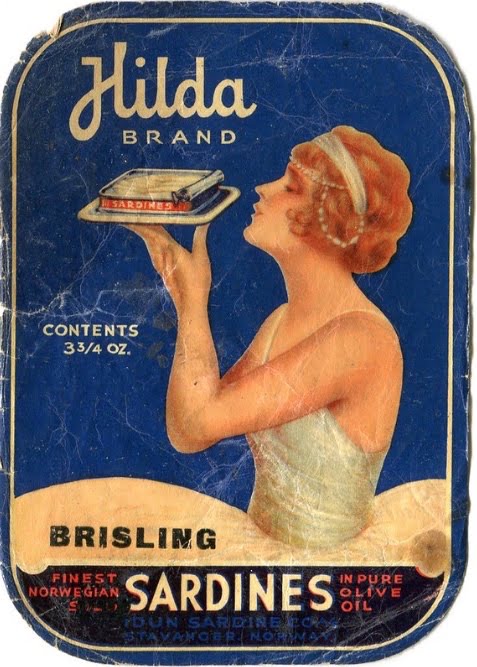

Of course, if you’re thinking of starting a family yourself (on your Norwegian honeymoon, for example), remember: nothing tempts a man so much as a tin of sardines. You may blush, but within the sanctity of marriage, it’s OK. I didn’t want to mention it, but that Hilda was hanging around in the hotel lobby: if it’s not your sardines, there’ll be plenty of other women tempting him to stray with their fishy snacks. Did I mention their aphrodisiac properties? Eat the sardines and make babies…

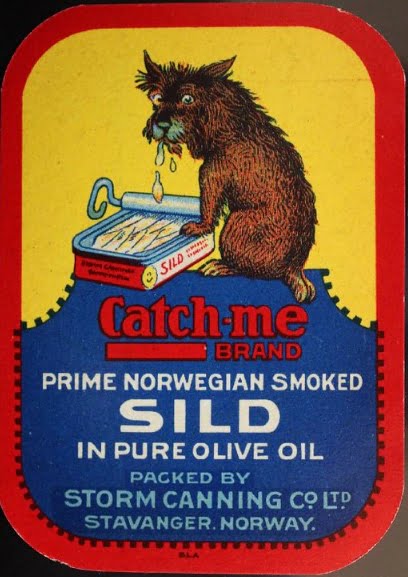

The Animal Kingdom

A giraffe seems to have wandered off his own abecedary page in search of C for Camel. A cute duckling, keen not to share its booty, attempts to swallow a juvenile herring on its own. In the established red and gold of King Oscar’s sardines, the King of the Jungle stands in for the King of England (there’s also a French cockerel for the Coq Brand). A polar bear on his ice floe eats his herrings straight from the tin. A Bengal tiger impersonates Kipling’s Shere Khan. One way or another most iddis animals belong to the world of children’s books, which in the second half of the C19th had pioneered so many of the new colour printing technologies. Animal iddis tend to be an educational extension of the family.

Some might question the Polar bear’s adaptation to the modern age, but anthropomorphism might have a basis in facts beyond mere marketing. When the great Finnish photographer Pentti Sammallahti worked on The Russian Way, he met a man in the post-industrial wreckage of Murmansk, who told him, This place is a paradise… for dogs. Sammallahti decided he had to have a dog in every picture and, to facilitate this, he carried tins of sardines everywhere he went. When he found a photograph he wanted to take, all he had to do was open one, pour the oil into the snow and wait. Within a couple of minutes a dog would always appear, mad for the smell of it. Dogs can smell sardines up to 12 miles away, but a polar bear can smell a seal at 20 miles.

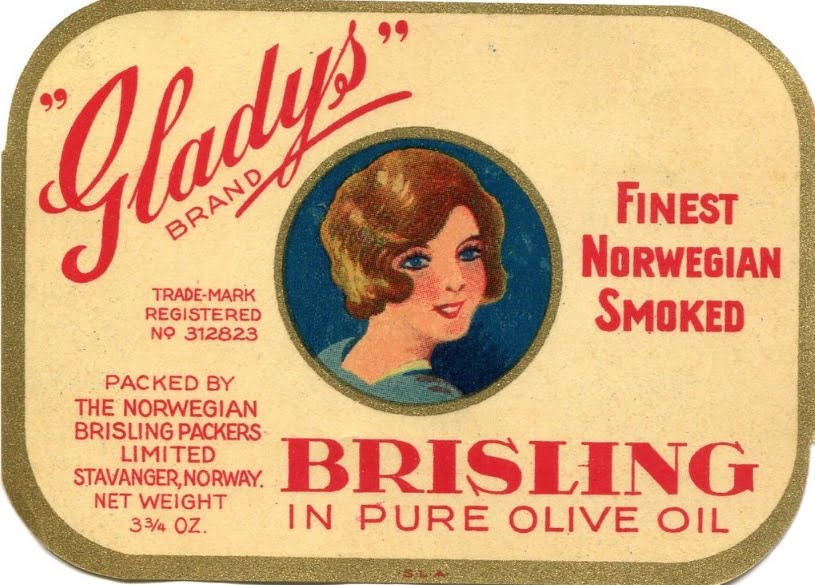

Women and Sardines

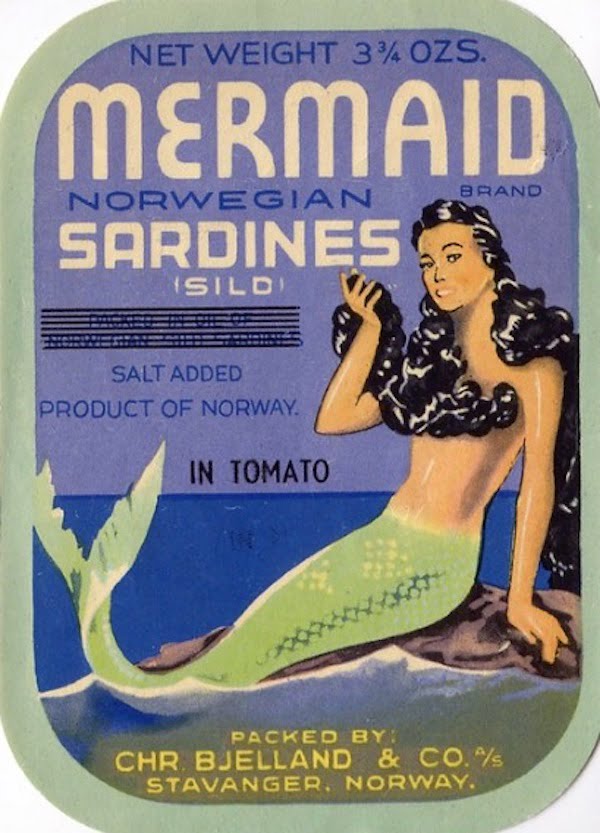

There are many beautiful young women on Norwegian sardine cans. A number of them have names: Aimée, Alice, Alma, Berit, Blanche, Blondkopf, Daisy, Doris, Eleanor, Ella, Else, Gaby, Gerd, Gladys, Gloria, Hilda (we know about Hilda), Ingri, Leonetta, Lucille, Lorry, Lu-Lu, Marcheta, Marit, Mary-Anne, Molly, Nancy, Natalie, Ninette, Norny, Odette, Peggy, Pola, Rosemary, Sonja, Thelma, Vera, Zena…

Berit may have been doing a bit of moonlighting as Miss Norway, although she wasn’t a regular – the iddis have a clear preference for blonde Miss Norways.

Meanwhile, when Daisy the waitress wasn’t serving us her tins of sardines, she enjoyed a separate life as a flamenco dancer.

Few have lost money persuading lightly clad women to offer us their products, but (apart from Hilda, of course) if they have a name, most modern iddis women dress and behave modestly. Classically and mythologically imagined women tend to prefer something diaphanous. Bathing beauties rarely have names, but like the others they all still want us to eat their sardines.

Part-sardine themselves, mermaids have tempted sailors and fishermen for centuries. They form a kind of bridge between the beautiful unnamed women and the fish in the tin. Helpfully, mermaids rarely bother with a blouse. Forget about your daily cares and join me on this little rock, they seem to say. We can live on sardines and love.

But perhaps there are sardine-buying women, who simply tire of objectification. The iddis understand. Some might indeed feel better off with a herring: you can rely on a good kipper. But just imagine the fun you can have with a sprat…

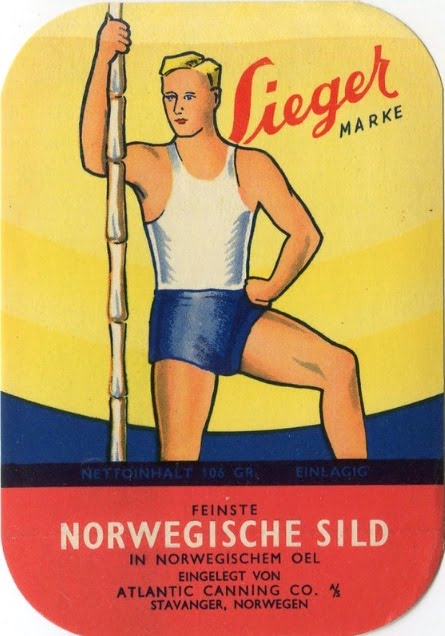

Sport (Men and Sardines)

The sport you come across most often on the iddis is sailing. Anything to do with the sea carries the bonus hint of fisheries out of frame and the shoals beneath. Olympic glory, however, and healthy men and boys taking part in healthy sports are widely celebrated on the iddis.

As the The Bonzo Dog Band‘s Vivian Stanshall once sang, It’s an odd boy who doesn’t like sport… Maybe it’s a chill memory of PE teachers in the 1960s, but there are one or two 1930s iddis, which can seem a tad too close to the Aryan ideal. Our Wagnerian hero. leaning on a staff made from the bones of his enemies, is actually a pole vaulter (it’s a bamboo pole). He may be Gustav Wegner, the German athelete who became the first ever European pole vault champion in 1934. Or Karl Sutter who was champion in 1938.

But these are troubling thoughts: let’s just stick with Mr Norway…

Culture I

The skiers on the Saga tin aren’t just any old Norsemen. It’s an 1869 painting by Knud Larsen Bergslien and they’re Birkebeiners, members of a C12th/13th Norwegian civil war faction, who the Baglers (the other faction) once sneered at as too poor to afford anything better than birch bark shoes. The Baglers came to regret it. These Birkbeiners are on an epic 1206 journey, carrying the two year old Prince Haakon to safety in Trondheim. As King Haakon IV, he later defeated Baglers’ boy, Sigurd Ribbung and even later put paid to Skule Bårdsson, former regent, then pretender. You see, most of you have learned something new. That’s how it is with Norwegian sardine can labels.

Terje Vigen or Viken, meanwhile, is an 1862 Ibsen poem about a Norwegian hero caught and imprisoned by the British for smuggling food across their Napoleonic War blockade. Without the bag in his boat, his family starved to death, but he only went and saved the life of the English lord who’d captured him.

Like Nansen, the Norseman brands and the Norwegian landscapes, these iddis reflect the heightened nationalism around Norwegian independence, but cultural branding was also international. We’ve already had King Lear, but The Ancient Mariner, Samson, Tosca, Carmen, Rosalind (from As You Like It), Mona Lisa, Crusoe and Pickwick are all in there. As well as with his Terje Viken, Henrik Ibsen gets his own brand, as do Goethe, Dante and the Polish diarist Comtessee Potocka.

Myths and tales, children’s books and pantomimes all get branded: Odin, Thor, Yggdrasil (the world tree), Jupiter, the Golden Fleece, Sparta, Hector, Ivanhoe, Tom Sawyer, Alladin (as he prefers it to be spelt when he’s on sardine business), Sinbad, Treasure Island… Ah! who could forget Treasure Island’s Pirate Penny and her treasure chest of sardines? There’s even a Pixie.

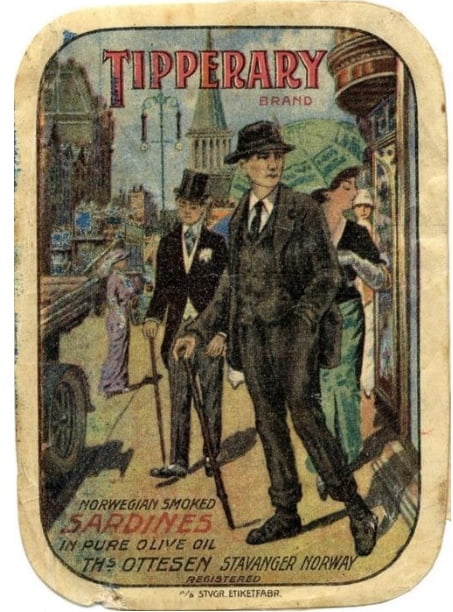

Culture II: Tipperary

Without question the most narratively complex cultural iddis was for the Tipperary Brand, named after the music hall song It’s a Long Way to… It had been written in 1909 as It’s a Long Way to Connemara by Jack Judge and Harry Williams. When Williams died, Judge claimed to have been the sole author, but this was stretching a point. Performing at the Grand Theatre, Stalybridge in January 1912, he took a 5 shilling bet he couldn’t write a song and perform it the next night. He tweaked Connemara, claimed his winnings and gave Stalybridge Tipperary. The song was an immediate hit, but it became even bigger when the Irish tenor John McCormack recorded it in 1914. Taken up by the troops in World War I, it then became a phenomenon. The Tipperary brand was registered in 1915. It’s interesting, but probably irrelevant that Judge had once been fishmonger.

It looks as if the image may have been a Stavanger iddis original, in which case it’s extraordinarily complex. Lots of illustrative Tipperary postcards were produced in World War I and there’s a sequence of four tinted photograph ones, which begins with with a street scene not unlike that on the label.

The Stavanger Etikett Fabrik image specifically places the song’s ‘Paddy’ on Regents Street – All Souls, Langham Place is in the background. The verses (which most people don’t know these days) aren’t without their Irish gags (Paddy wrote a letter to his Irish Molly O / Saying ‘Should you not receive it, write and let me know!’) but the iddis artist is not thinking of such demeaning carryings-on.

The first verse has Paddy getting just a bit too excited in all the gaiety of London and shouting the famous chorus in the street. Stavanger’s well-researched Irishman (soft hat, knobbly stick and, in the absence of bicycle clips, rolled up trousers) is altogether more thoughtful. He tires of London’s empty sophistication – the shallowness of Miss Snooty with her green umbrella, the complacently vacuous Mr Top Hat & Tails. Any shouting must be coming from that suffragette in the street, haranguing passers-by. How different his Molly is to all these modern women.

The iddis restricts its narrative to the chorus: against this backgrund street noise, Paddy thinks of Molly back home. It’s a spur of the moment thing. Suddenly he’s on his way down Regent Street to say, Goodbye! when he gets to Piccadilly and then Farewell! at Leicester Square. He’s pointed in the right direction.

This Paddy’s not a music hall joke. He has more the look of a Richard Hannay (The Thirty-Nine Steps was first serialised in 1915). He’s going to get back to Molly. There’s no way she’s going to marry Mike Maloney (as she threatens in verse 3). He might be on his way to enlist first, but he has the face of a man who is going to get back home.

Playing the Markets

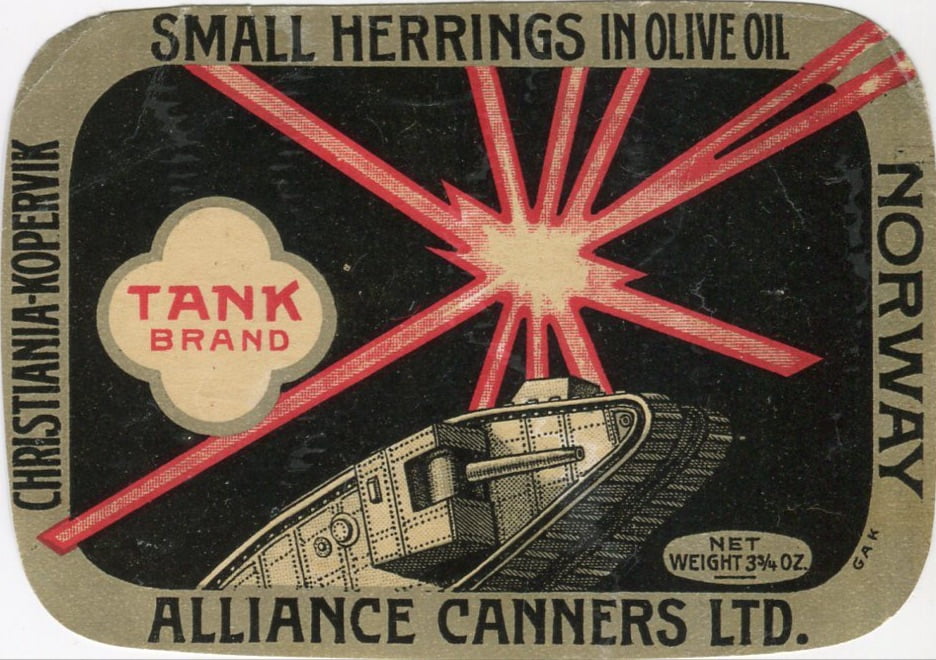

While we’re on the subject of war, it can bring uncertainty to a market. Sardines are for everyone, however, and you sometimes need to hedge your bets. Sardine labels could be admirably even-handed. If the iddis end up seeming to take sides, the Royal Navy was, after all, blockading German North Sea ports, The Skagerrak and the Kiel Canal.

The Conquerors Brand label, with its flags of Russia, Japan, United Kingdom, France and Belgium, appears first to have been used for Unity Brand tins. Conquerors probably waited until 1918 (even though the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk should technically have taken the Russian flag out of the picture by then). Although Norway was neutral, the canneries kept an eye on developments: Tank Brand responds both to the Sardine Litigation and the entry of the British Mark I tank at the Battle of the Somme.

Perhaps not surprisingly, it’s the Royal Navy which ends up getting the biggest armed forces label shout out: HMSs Amethyst, Dreadnought and Iron Duke, Ensign, Admiral, Commodore, Captain, Middy (midshipman), Jack Tar and True Blue brands.

After the World War I, British herring fleets never managed to regain the glory of their record 1913 catch. With its more efficient fishery, Norway fared better. In a gloomy 1936 parliamentary debate about the Herring Industry Board, the expanding USA and Palestine markets were identified as sole rays of hope. They had both almost certainly been stimulated by Poland’s ‘encouraged’ interwar Jewish emigrants. Norway’s sardines were there to meet them. If a US distributor serves Mid West Jewish communities, slap on the founder of Zionism; for Tel Aviv, a quayside shot speaks to migrants arriving in a new land and the sardines the ship is carrying in the hold.

If Hull Co-Op wants its Jameson Street premises and the Wilberforce statue, let’s not worry about the streets between. If the distributors are in far-off Africa, celebrate that extraordinary journey with a map of all the sardine pick-ups and drop-offs between Trondheim and Mombasa.

If in doubt, every market has its own mermaids.

Sardines and Indigenous Peoples

Using the film poster typeface from Robert Flaherty’s Nanook of the North (1922), the Polar Queen Brand probably dates from the early 20s. The photograph in the montage looks like a still of Nanook’s wife-in-the-film, Nyla. The brand may have been less concerned with promoting the rights of indigenous peoples than capitalising on Nanook’s box office success. Having said that, iddis representation of Native Americans does exceed that of the cowboys by a factor of four or five.

The Narragansett are an indigenous Rhode Island Algonquian people. What Cheer Brand was developed for the same Rhode Island distributor, but she and Miss Petite look more like they’re escapees from a socialite fancy dress party.

Radio Sardine

The revolution in communications became another signifier of the Modern Age with which Norwegian sardines liked to associate themselves. Where the label’s for the Radio Foods Corporation, a herring tentatively nosing itself on to the airwaves can be seen as fair play. Where the distributor is the upmarket Japanese grocery chain Meidi-Ya, playing on the concept of mass media (a term first coined in 1923) has to be acknowledged as clever. But the vision of Stavanger broadcasting its sardines across the world by means of pre-Star Trek teleportation… That is design genius.

Sophisticated Snacks for Sophisticated People

Price was key to Norwegian sardine success, as it was with the barrel salted and the smoked herrings that came before. Cheap Brand unusually draws attention to this, but even here there’s a countervailing touch of the delicatessen: these are Spring herrings with a sauce made from tomatoes which once hung on the vine.

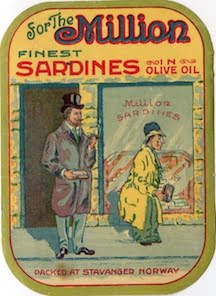

Social aspiration trumping The Depression, even in the 1930s the UK home market for herrings and sprats continued to slide. Insistent use of Brisling and Sild on UK cans (still prevalent) is a give away. It’s as if, if you told them what they actually were, you’d be done for. In one of those triumphs of marketing Norwegian sardines were able to have it both ways: if you’re down on your luck, open a tin and feel like a lord; if you’re not, they make for the daintiest canapés (and not just in the Club des Millionaires). The Charlie Chaplin-esque For the Million joke almost speaks to Shelley’s Ye are many, they are few.

What is a Fish-Pyramide? It might visualise a Stimenbildung, concentrated shoals of herring that set away almost a boiling on the surface of the water. Danish historian Saxo Grammaticus described one at the end of the C12th; William Carlos Williams, writing of precisely the Norwegian fjord fishing which underpinned the sardine trade, describes one in his 1922 poem Fish. But key to the design for the Fish-Pyramide brand is its Art Nouveau sophistication. You want to be in with the in-crowd? it asks. Get with the sardines!

In the C14th/15th the Dutch seized the mass market for their barrels in part by creating a delicatessen cult around their maatjes herrings. A lot of iddis designs speak to the aspirations of the poor. Sardines can enjoy popularity across society, but they’re about as sophisticated as The Shangri-las singing Sophisticated Boom Boom.

King Oscar’s Good job I dropped in at the right place shop display poster is a straight pitch to people who place a premium on sharp dressing because of poverty. Sardines became big in the USA’s growing urban African American communities. Synonymous with poverty in The Notorious B.I.G.’s Juicy (Born a sinner, the opposite of a winner / Remember when I used to eat sardines for dinner) their resonance goes deeper. America’s own Eastern seaboard sardines are juvenile herrings, along with them, Norwegian sild and brisling played a part in creating the context for The Junk Yard Band’s Sardines, without question the best tinned fish song ever recorded; a paean to sardines as the nutritional beating heart of a community – specifically Washington’s Barry Farm government housing project. In the late 1990s the image was used on commemorative sardine tins for a Norwegian blues festival.

The Limitations of this Survey

These groupings have been based on looking at fewer than 12,000 iddis – and a number of them were duplicates. Even so, other recurrent motifs could have been explored. There are many bearded fishermen, but William Duncan Anderson knocks them all into a cocked hat. There are the fresh-faced women in Sou’ Westers, who deserve a grouping of their own. There are even iddis you could categorise as pretty much like anybody else’s product labels.

PART THREE: TIME AND THE IDDIS

If Iddis collecting didn’t ever really take off much beyond Stavanger, it’s probably because it originally relied on the concentration of iddis printworks. Labels are collected from the Cannery Row production of the American West Coast, but their sardines are Pacific pilchards (Sardinops sagax) and outwith the purview of this encyclopaedia.

Looking at marketing imagery from earlier times is often amusing and there are visual similarities in label outputs for other products across the world, but there’s an idiosyncrasy with iddis which is insistent. It grows out of an unusual combination of the provincial, national and international. The degree of economico-cultural focus in such a small city; the curiosity and freedom that could come from the previous lack of an extensive graphic design history; the intense competition of the canneries; the uniformities in the design formats; the need to engage with such diverse export markets: all of these factors will have played roles and the iddis collectors may have supported the atmosphere of creative challenge.

The salad days of the iddis lasted from the early 1900s to World War II. Rationalisations of the canneries and their promotional efforts began in the 1930s and had their effect. Shopping habits went through extraordinary changes in the C20th: self-service grocery stores, first seen in the USA, date from 1916. When a grocer served each item, novelty was key; when customers selected from the shelf, familiarity moved to the fore. The horizontal format became more favoured because cans displayed on shelves are more stable on their sides and had to be legible .

Supermarkets, which began to spread in the USA from the 1930s, didn’t develop in the UK until the 1950s, but then the chains grew quickly here and across the other sardine export markets. Centralised purchasing increased the need for rationalisation.

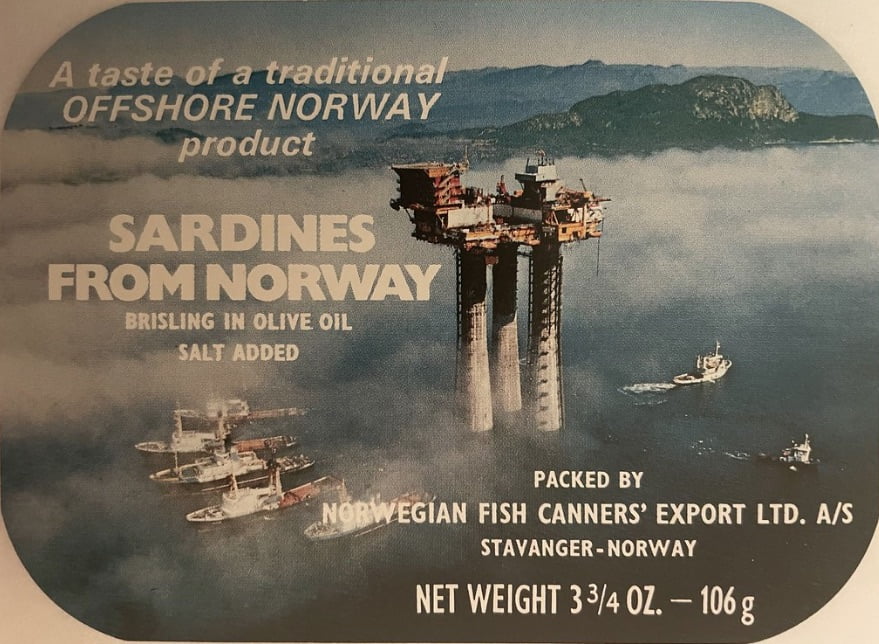

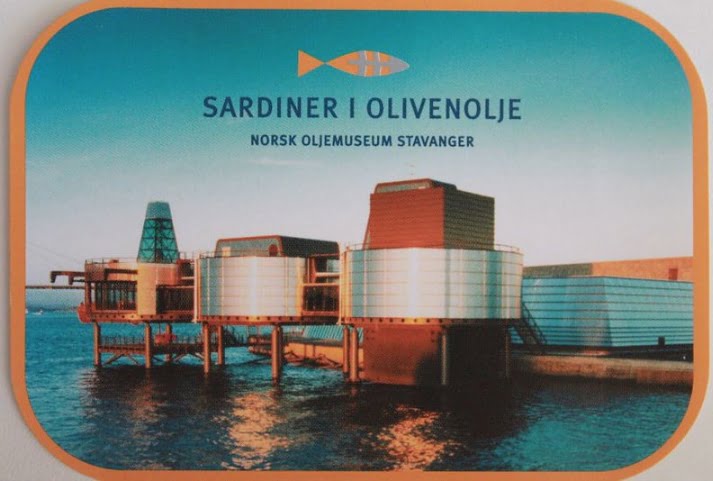

There were the fish population collapses from the 1960s onwards, pretty much coinciding with arrival of oil. Stavanger’s sardine supremacy coincides with Iceland’s Herring Era, developed by Norwegian fishermen from 1902: they were fishing the same spring spawning herring populations as juveniles in the fjords and as adults off the North of Iceland. The consequent collapse of the two fisheries in 1969 underpinned both Iceland’s and Norway’s moves towards managed sustainability.

There are no working canneries in Stavanger anymore. Angus Watson & Co became part of Unilever’s John West Foods, which Heinz acquired, then Lehman Brothers. After the Lehman Brothers crash, in 2010 it was bought by Thai Union Group. The King Oscar brand became part of Norway Foods in 1981 and in 2014 it was also sold to Thai Union Group. The sardines of both, these days, are packed in Poland.

But the iddis remain, testament to an extraordinary flowering in the history of commercial design. We may not see its like again, but we can celebrate its printed record.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This entry draws on a number of publications:

“Out to conquer the world”: The King Oscar Brand Through 100 years, John G Johnsen (2002)

The World of the Iddis: Stavanger – the center of the Sardine Tin Labels, John Gunnar Johansen (1996)

The History of Smoked Norwegian Sardines, Norwegian Canning Museum (online pdf)

My Life, Angus Watson (1937)

My grandfather gave me a signed copy of Angus Watson’s My Life in 1970. Watson had been a member of the same Methodist congregation in Rothbury, Northumberland. A fellow teetotaler, my grandfather hoped I would draw on his example. I have come to realise Watson was the man who, in 1938, found my father a berth in the merchant navy when he’d been expelled from Gosforth Grammar School (drinking, smoking, billiards). It probably wasn’t the best time to take up a career in the merchant navy – he was on the Royal Sceptre, the second ship to be sunk in the Second World War – but he survived and if he hadn’t later met my mother, who was nursing him after he’d been caught between a ship’s side and its launch, among other things there would never have been a herripedia. So big thanks to Angus Watson!

Big thanks also to the Norwegian Canning Museum. It wasn’t until in 2010 I saw its display on Angus Watson, that I finally realised why I had to read My Life. It took me two years to find it. Big thanks to Piers Crocker, who was extremely helpful when I decided to write an Iddis entry for the herripedia. Nathan Hill, editor of the magazine Fish, commissioned the two of us to put together a feature, Iddisology, which was a joy, so big thanks to him too. More recently, Erik Hennum-Bergsagel of MUST/Norwegian Canning Museumwas very helpful when I finally got round to writing this entry, so thanks to him and to MUST and Iddisklubben Norway Brand for permission to use the images.

Discussion of the Tipperary Brand image on Twitter helped clarify my sense of its richness. I’d particularly like to thank Geraint Smith, James Hogg and Simon Platman for their contributions to the debate.