On the great Jewish dish, chopped herring or forshmak, a contested history and a range of possibilities

CHOPPED HERRING

Sephardic refugees from Portugal gave us the battered fish frying at the heart of the nations’ sense of identity: let us praise them! Let us also, however, praise the Ashkenazim for so resolutely standing by the herring which swims through theirs. A 1937 parliamentary debate on the herring industry offered next to no hope at all for increasing home sales. New exports to Palestine and the USA provided its only cheer, even though there was a distinct home market segment, depressingly and disturbingly sometimes referred to as the Jew Boy trade. Here and across the diaspora, the Ashkenazi herring dish of dishes is chopped herring or forshmak. Its argued over recipes are themselves statements of identity.

Chopped herring is a straightforward translation of the Yiddish gehakte herring, which is what Polish and Lithuanian Jews tended to call it. Forshmak is from the Old German Vorschmack, foretaste or appetizer. The Soviet historian of Russian cuisine William Pokhlyobkin (1923 – 2000) traces its origins of to East Prussia and a fried herring dish, which he sees Ashkenazi Jews as having carried with them eastwards, transforming it along the way into a cold paté. This, in turn, spread beyond their own communities into the wider populations of Russia, Ukraine and other Central and Eastern European nations. On the basis of the name alone, the revered American Jewish food historian and founding editor of Kosher Gourmet Gil Marks agrees with the idea of Germanic origins.

Food history chopped herring accounts follow Pokhlyobkin and Marks: a fried medieval German rissole made paté during oppression-enforced eastward migrations. But…

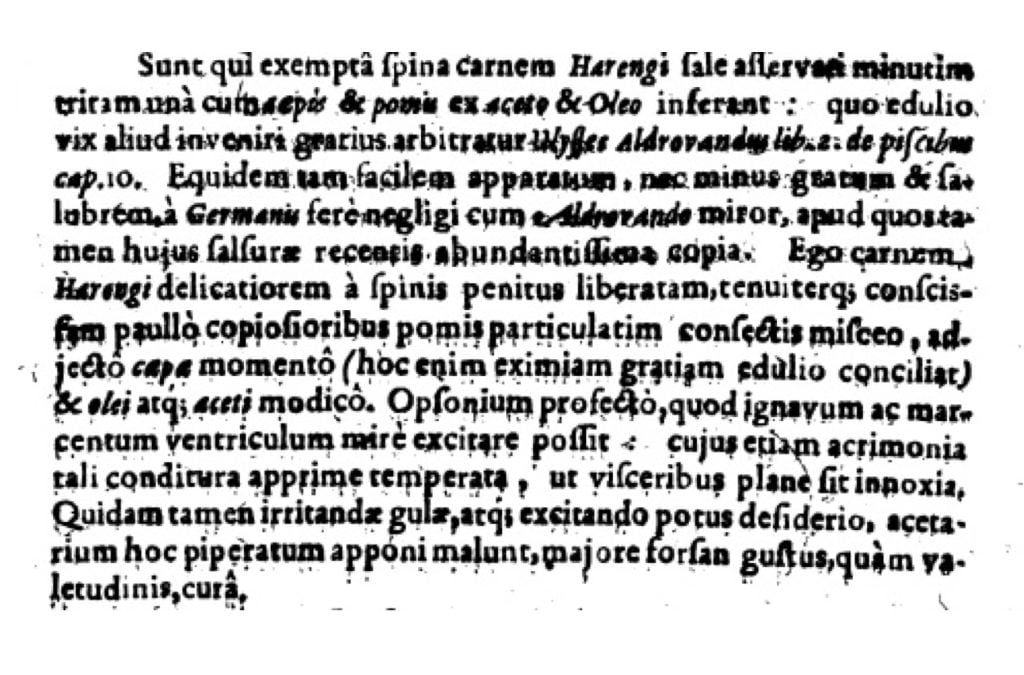

Some fillet salt herring and grind the flesh with onion and apple and sprinkle it with oil and vinegar. Ulisse Aldrovandi (De piscibus, Bk 2, Chap 10)thinks there is no better way of serving fish and I’m with him on this, surprised such an easy, healthy and delicious dish is practically ignored in Germany – after all, we have no shortage of freshly pickled fish. I combine carefully filleted and finely chopped salt herring with a slightly larger quantity of chopped apple. I add a little bit of onion at the last moment – the timing is key – along with a small amount of oil and vinegar. This is a dish to revive weak or lazy appetites. Sharpness is softened in the combination, taking away any potential harmful effects. Some prefer adding a pepper salad to stimulate the palate and to encourage the desire to drink, but this is putting taste above health.

from Ch XII, Concerning herring preserved with salt, Neucrantz’ De harengo (1654)

There’s a comic spirit which runs throughout Neucrantz, but he knew his herrings. De harengo is an extraordinary summary of C17th knowledge of the subject, based in exhaustive reference to classical and contemporary sources.

The great proto-taxonomist Aldrovandi lived in Bologna, where they might have been chopping herring for a hundred years, already. In 1549, his meeting in Rome with French ichthyologist Guillaume Rondelet had upped his own interest in fish and they became friends: the recipe might have originated in Rondelet’s home town of Montpellier or elsewhere in France. A paté of chopped herring and onion appears in the anonymous Northern French poem The Life of Saint Herring. Neucrantz’ Practically ignored in Germany may mean the recipe was generally uncommon. It might also suggest, at that time it was only eaten in limited circles – such as the Jewish community.

Neucrantz, an academic and a practising doctor of medicine, may have moved in wider circles. He was certainly at ease with Greek, Roman, Arabic, Jewish, German, French, Italian, even English sources. Aldrovandi’s De piscibus was published posthumously in 1613 and Neucrantz will have credited him because his was the earliest ‘authority’ he had found for the recipe. The detail about adding the onion suggests either he’d taken the time to develop his own recipe or he’d spent time observing someone else preparing it. What is clear is his understanding that, at that point, the dish was more widespread elsewhere and particularly, he implies, in Italy.

The Ashkenazim grew largely out of trading diaspora communities and freed slave populations, who’d originally been brought into Greece and Italy after the failures of the C1st Jewish-Roman War and the Bar Kokhba Revolt of the C2nd. In response to persecutions which had intensified during the Crusades, the Ashkenazim were still migrating north and east from Southern Europe in the C16th. Traces of what must have been salt herring have recently been discovered in the ruins of Pompeii, but it was extensively exported to the Mediterranean at least from the C13th (see Aquinas, St Thomas).

According to Neucrantz, both Rondelet and Aldrovandi challenge Pierre Belon’s view in De la Nature et Diversité des Poissons (1551) – or possibly De aquatilibus (1553) – that herrings swam in the Mediterranean, so herring conversations were possibly exchanged between the two friends. They may or may not have included chopped herring. Neucrantz was from Rostock, but he wrote his herring treatise in Lübeck, which, though fallen from grace by the mid C17th, had been at the heart of the Hanseatic trading overwhelmingly responsible for the widescale introduction of salt herring to Southern Europe.

The German Hanse actively barred Jewish involvement in the herring trade, but from the C15th the Dutch became the dominant force. This may have opened opportunities for engagement, but regardless of the trade, the taste for chopped salt herring, apple and onion may well have travelled north and east in the C15th and/or C16th with Jews migrating from Italy and Greece. There’s a Greek Arenga recipe, which chops up red herring, apple and spring onion with olive oil: it might be relatively modern, but England was exporting reds to the Ottoman Empire by the C16th.

Neucrantz describes a dish much closer to gehakte herring and forshmak than a fried rissole. The Yiddish names have Germanic roots, but the journeys towards the dish itself might have been more complex. It’s nice to think of Neucrantz playing a role in popularising herring chopping on its historic, continent crossing journeys. It would be some compensation for the way his great treatise has been so resoundingly ignored over the centuries. He wasn’t describing a dish by name, however: it might have met its names later.

Chopped herring recipes

Vorschmack has also gone beyond Germany to Russia and Ukraine and can be hot and rissole-ish as well as cold and spreadable. It can use meat rather than herring. Appetite can be appetised by all sorts. In a similar way, Forshmak has gone beyond Jewish communities, but its diversity within the diaspora is enough to keep anyone going. Salt herring, apple, onion, oil or butter and vinegar or lemon juice are pretty much constant (although some recipes go for vinegar marinated herring). Maatjes herring can be specified – and it’s salt herring at its tastiest, so who wouldn’t use it if it’s available? Usually tart apples are suggested. The onions can be mild, yellow or spring (scallions).

The next most common ingredient is the hard-boiled egg, which can be separated into chopped or grated whites and yolks. One recipe insisted on soft-boiled so that the yolk could more effectively colour and flavour the mixture. Almost as common as the eggs is bread. One recipe suggested brown, but most specify white and crusts are always removed. It’s usually soaked in water and then squeezed before mixing it in. The bread element can also be supplied by matzo, crumbled ginger biscuits (Poland) or marie biscuits (South Africa); it can also be replaced by potato. The dish is also served with or on bread (including the Jewish bread challah). It may sound a tad faux-sophistiqué, but it can be served on lettuce leaves. Some recipes include a teaspoon or more of sugar, black pepper, salt or sour cream. Some fusion foodies in the USA add chopped fresh chilli.

There is considerable debate about blenders. Some recipes use them without a thought, but although you may not want large chunks of herring, the joyous texture of the salt fish is lost in what the Jewish Food Society refers to as homogenous paté. Personally, I’d mash or blend any egg, matzo/bread, oil/butter and vinegar/lemon juice and use it to bind the finely chopped salt herring, lemon juice rubbed apple and onion. I don’t think I want to know about ginger or marie biscuits. I wouldn’t bother with sugar either: there’s enough sweetness in a maatjes herring. Although, I might give making some challah a go – a bread sweetened with honey and plaited, it sounds good.